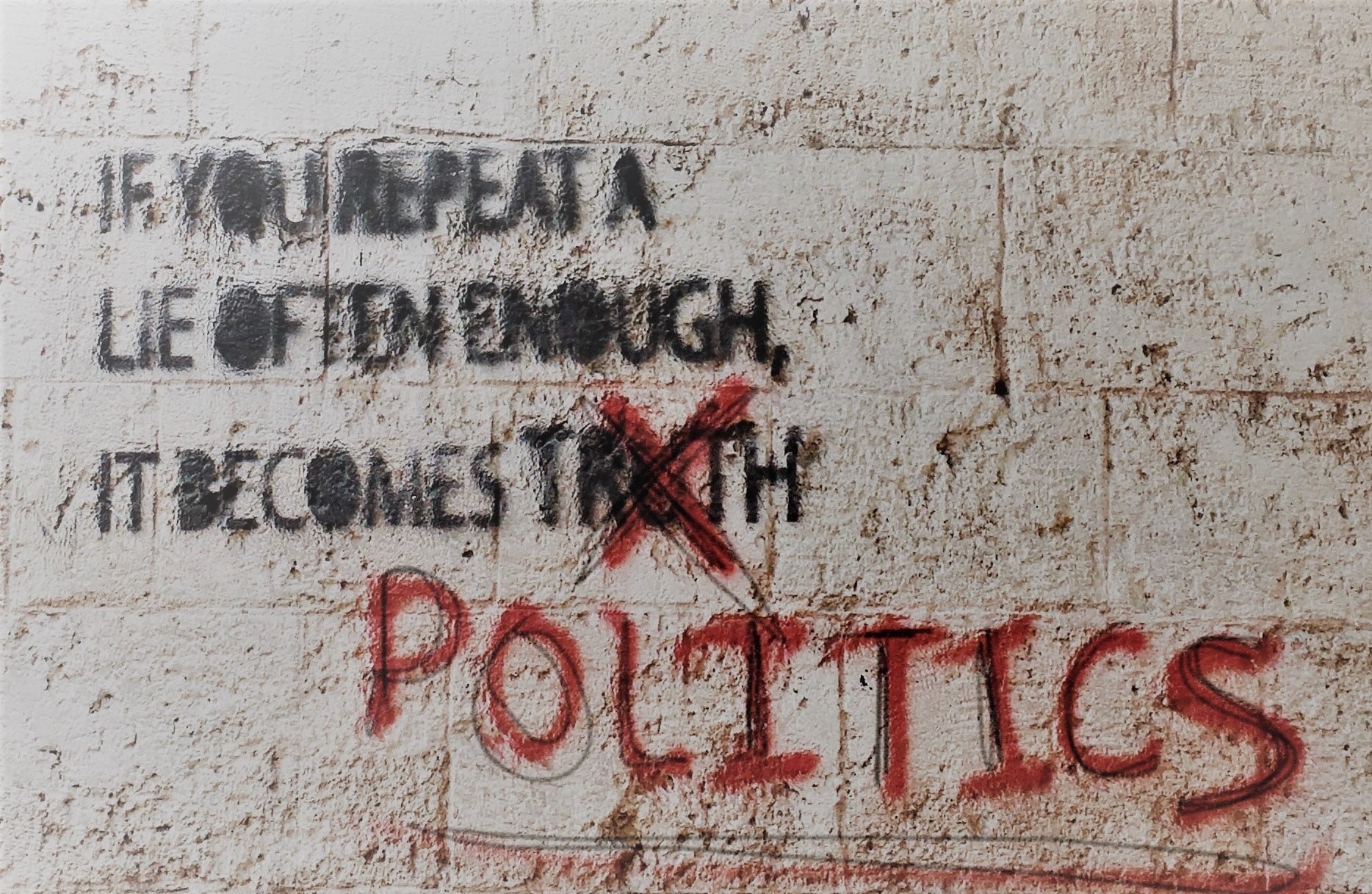

Editorial Rant: On falsehood in politics

First, let’s straighten out that “world of politics” reference; politicians do not, and should not feel entitled to, occupy some separate sphere from the rest of us on this planet. But in some ways, they seem to: politicians seem to have some special license, à la James bond, to kill – to kill truth with words.

The advertising industry’s self-created watch-dog organization, Ad Standards, does not cover political advertising. The Canadian Code of Advertising Standards explicitly excludes certain things, as made clear in this excerpt:

“Exclusions

“Political and Election Advertising

“Canadians are entitled to expect that “political advertising” and “election advertising” will respect the standards articulated in the Code. However, it is not intended that the Code govern or restrict the free expression of public opinion or ideas through “political advertising” or “election advertising”, which are excluded from the application of this Code.”

Political ads are not held to the same standards of truth as mere commercial ads. Commercial ads are allowed what is termed “mere puffery” to exaggerate (slightly) the virtues of the products they’re promoting, but politicians seem to be allowed free license to tell outright harmful lies about any issue in which they think they have an interest.

Witness the recent mysterious appearance of an ad that blatantly suggested that NDP Leader and candidate Jagmeet Singh owns a huge, opulent mansion somewhere – a totally false and damaging bit of fake news. Efforts are being made to track down who was responsible for getting it published. But it’s unlikely that there will be any consequences, given that it was probably done for a political purpose.

Think back to the “No” campaign on the electoral reform referendum in BC: it was based almost entirely on falsehoods about the putative effects of proportional representation. I call them falsehoods because they were statements which were not only not supported by evidence, but were contradicted by the preponderance of evidence.

If politicians were held to advertising standards, they could not have done that: the Advertising Code states,

“All advertising claims and representations must be supported by competent and reliable evidence, which the advertiser will disclose to ASC upon its request. If the support on which an advertised claim or representation depends is test or survey data, such data must be reasonably competent and reliable, reflecting accepted principles of research design and execution that characterize the current state of the art. At the same time, however, such research should be economically and technically feasible, with regard to the various costs of doing business.” [Emphasis added.]

Why should politicians, who want us to trust them enough to put them in positions of power – power to govern, power to enact legislation, power to influence the lives of millions of people in so many ways – why should those politicians have license to lie? Why should citizens, who need to be well-informed in order to vote meaningfully, have to tolerate a system that allows politicians the freedom to mislead us on crucial issues?

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, is one of the better-known early proponents of the value of a well-informed electorate. He is often quoted, and perhaps more often mis-quoted, on the issue. In a letter written on August 13, 1813, he stated, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”

Isn’t belief in the veracity of a pack of lies one way to define ignorance?

In another letter, Jefferson wrote to John Adams on August 1, 1816:

“I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education.”

By “education” we should not mean a mass of contradictory propaganda statements, some of which may be true, many of which may be gross exaggerations, and most of which may be utter falsehoods. Voters having to decide where to mark their ballots should not be required to sort out truth from lies every time they read a political ad or hear a politician open his or her face to speak.

Ad hominem attacks are another distressing habit of many politicians and their advertising. I’d like them to be held to the advertising standard that says,

“Advertisements shall not: …

“(c) demean, denigrate or disparage one or more identifiable persons, group of persons, firms, organizations, industrial or commercial activities, professions, entities, products or services, or attempt to bring it or them into public contempt or ridicule;”

Just imagine if politicians had to convince voters on their own merits, and on the merits of their party’s platform. Imagine the relief of not having to read or hear vicious and quite likely ill-founded attacks on other politicians and their parties.

Just imagine if there were an independent, truly non-partisan body with the authority to oversee political advertising, and require it to be truthful. It shouldn’t be necessary, but experience leads me to yearn for such a thing to curb the current and widespread rampant abuses of politicians’ interpretation of the term “freedom of speech.” I maintain that freedom of speech should not include the freedom to lie to the public on important issues, or about each other.