Column: New economics?

When you pause to reflect on what’s truly essential and meaningful for you to thrive, what comes to mind?

Is it about having more? Or having better? Is it about all the buying or the genuine caring? Is it about over-consuming or connecting and sharing? Is it about loving stuff and status or simply loving? As we experience disruption on a scale not seen since the Second World War, people in Canada are taking note of what’s really important to them. That can lay the foundation for new ways of thinking about a better economy for tomorrow.

We often confound “economy” and “economics.” Words matter. In this time of crisis, we’re hearing rhetoric aimed at convincing us that caring for our personal health and that of our loved ones is locked in an antagonistic tension with protecting the economy’s “health.” Yet the word “economy” refers to all the interconnected social actions every person does daily. It’s about the way you live your life and the way everyone around you lives theirs. It includes the stories we tell, the knowledge we share, the making, exchanging and trading. It describes how we experience and govern our collective lives on a shared planet.

“Economics,” on the other hand, is about how we think about the economy and what its purpose should or could be. As we’re witnessing at this extraordinary moment in history, often what we feel matters most in our times of need is not aligned with the purpose we gave our economy before this crisis.

It’s also interesting that the words “economy” and “ecology” both come from the Greek “oikos,” meaning “domain” or “household.” Ecologists seek the principles, rules and laws that enable species to flourish sustainably. Economists are meant to “manage” our activity within the biosphere, our domain — ideally within the rules and strictures ecologists find.

Before the pandemic, we thought of our economy as an engine, the main purpose of which was to burn through natural resources quickly to produce as much money as possible using the cheapest, most abstract notion of labour. That equation omits human beings with all our complexities and the “pale blue dot” on which we all depend. It wasn’t exactly intentional.

This equation was agreed to at the end of a war, under the assumption that more trade between nations would ensure global peace and prosperity. In 1944, representatives from 44 countries met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to create a more efficient foreign exchange system and to promote economic growth. Out of crisis, a new way of managing our economics emerged. Although the system was changed in the 1970s, it maintained its earlier purpose.

Now, many politicians are ascribing war language to the pandemic response. But what will we do when this “war” is over? Will we allow an old equation to continue to guide us, or could we choose to come together to define a new purpose?

People everywhere are in distress. Our health and livelihoods are threatened. The social fabric of togetherness is impeded by a need to stay physically distant from each other. The old systems haven’t been able to respond to our needs in meaningful ways, so governments have had to use unusual interventions to ensure the collective good. The old way of thinking about the economy, the established economics, has been exposed as inadequate and flawed.

But through this distress and disruption, we’re seeing glimmers of transformative potential. Over a few weeks, incredible acts of kindness and collective caring have become normal. People are applying novel means of digital creativity to support each other. Some businesses are pivoting from short-term, profit-first motives to purpose-driven actions in response to real needs.

We’re witnessing the surfacing of tangible inspirations for the re-imaging of a Canadian economy — one explicitly designed to deliver the well-being and resilience people need to flourish — and that nature can provide today and for generations to come.

At the end of the Second World War, it took just three weeks for a small group of men to design what would become a new purpose driving the postwar global economy. As this crisis comes to an end, will we embrace the opportunity to do better?

Together, we can design an economics for what matters.

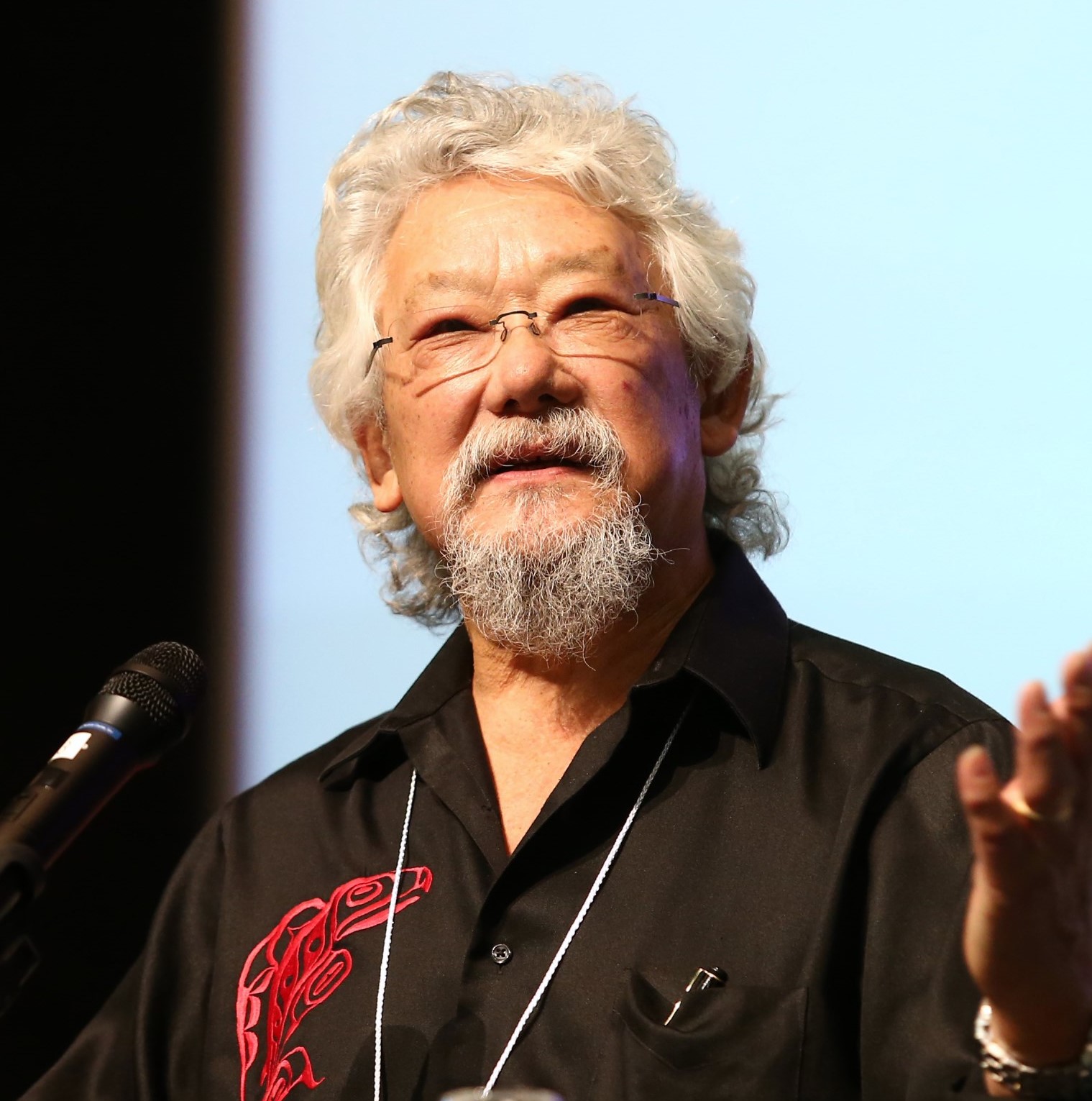

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Ontario and Northern Canada Director General Yannick Beaudoin.