Editorial: An object lesson from Uzbekistan

A Kootenay man, environmental consultant Michael Keefer who lives in Rossland and Cranbrook, was invited to go to Uzbekistan for a conference on solutions to the Aralkum Desert problem. While there, he toured the area and took many hundreds of pictures. When I sat down with Keefer, who told me fascinating tales of his travels there, it was obvious that the basic cause of the tragedy of the Aral Sea has a lot in common with some local phenomena, as well as global ones. It’s an object lesson for governments everywhere.

Problem? There are many deserts – why is the Aralkum Desert a problem?

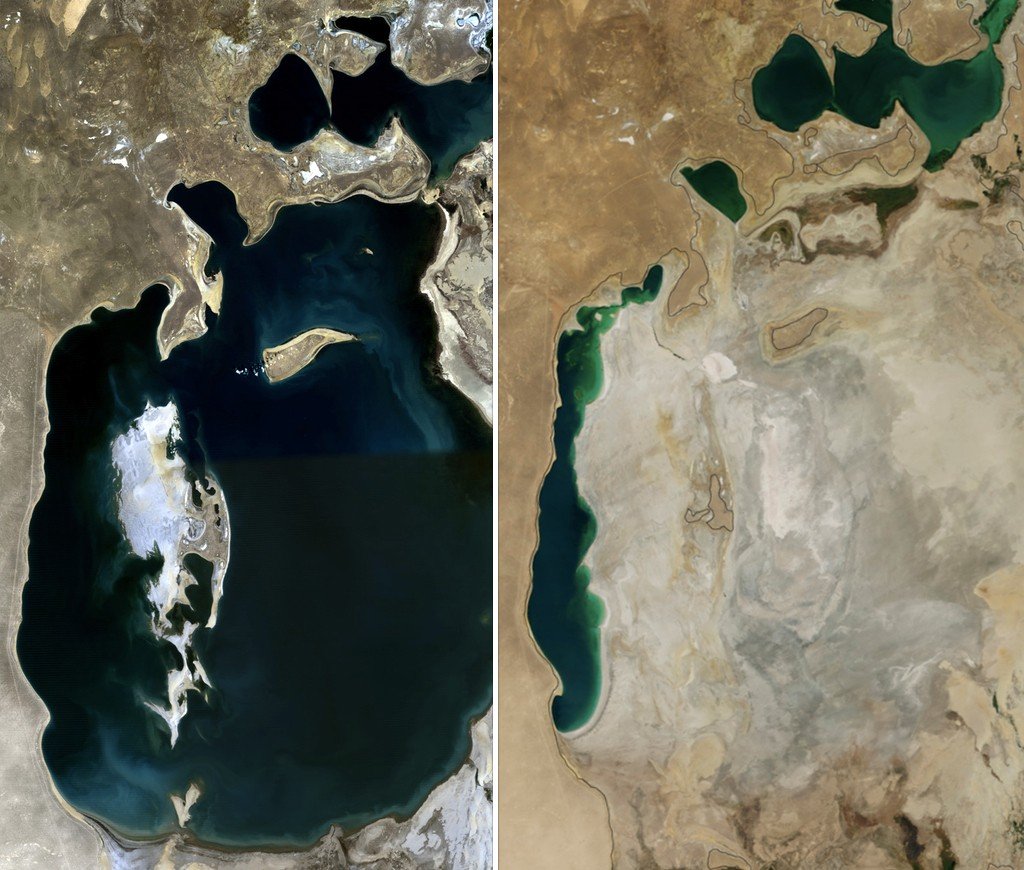

The Aral Sea used to be the world’s fourth largest inland body of water, with a healthy population of fish, surrounded by fishing and farming villages. Now most of it is the Aralkum Desert.

In the 1950s, Soviet engineers constructed irrigation systems diverting water from the two rivers that fed the Aral Sea, to boost cotton production in the country. Keefer said, “The engineers predicted it would dry up the Aral Sea, but they did it anyway.”

As it dried and the shorelines receded, the sea became increasingly saline. Fish died, and so did the livelihoods of those who relied on fishing. Cotton production increased, people continued to divert more water for irrigating the cotton crops, and the lake continued to shrink and become saltier. The lake reached a record low level in 2014. It had lost 90% of its former volume of water. Large former fishing vessels now sit stranded and rusting on vast expanses of sand. One study found that six million acres of surrounding agricultural land were destroyed by the desertification and associated salinization of soils.

Below: images from NASA show the Aral Sea in 1970 (left) and 2014 (right).

Most of the dried-up lakebed has become the Aralkum Desert, with salty, toxin-laden dust-storms causing illness and death in humans, animals and plants in the surrounding area.

Precipitation declined

While he was in Uzbekistan, Keefer was informed that the area now gets only 20% of its former precipitation. (Some 2014 data disagree with that figure, but it isn’t clear which opinion is more accurate.)

When it was the world’s fourth largest lake, the Aral Sea itself caused more precipitation to fall – large areas of water and forest tend to encourage rain. Drain the lake, clear-cut the forests – there will be less rain. A 2008 article in Physics Central discusses the role of forests in cloud formation and rainfall, and author Stephen Skolnick comments, “ … if we don’t stop the mass deforestation that’s still going on, we may risk turning much of the planet into a desert, permanently. The same feedback loop that would allow the introduction of plant life to make a region more habitable could go the other way: if fewer trees means less rainfall, cutting down trees could starve an ecosystem for water and push it over a tipping point, resulting in mass desertification.”

What now?

At the conference Keefer attended, he was asked to give a presentation on a hand-operated desalination device – a reverse-osmosis pump using a special membrane for desalination – which Keefer’s father had invented in the 1970s. Keefer and his father hope to redevelop the technology to handle the brackish water in the Aral region, to help residents access more potable water. As it is now, the salty and mineral-laden dust storms, scarcity and high mineral content of the water, and the high concentrations of agricultural toxins, are probable contributors to the spate of health issues in the region. These include higher rates of cancer, hepatitis and respiratory ailments, as well as diarrheal illnesses and infant mortality.

The Uzbek Ministry of Innovation

Keefer was invited to the conference by a friend of a friend who is in the Uzbek Ministry of Innovation, who interviewed Keefer about his career and was fascinated about his father’s hand-operated desalination pump. (The names of his companies reveal his areas of expertise and interest: Keefer Ecological Services, Keefer Hazmat Services and Aspen Grove Residences.)

Keefer told me that the conference he attended included good scientific presentations, interspersed with what he referred to as “government propaganda.” One lecture focused on current efforts to transform the Aralkum Desert into salt-tolerant forests; the first goal is to minimize the storms of polluted, wind-borne sand and dust that cause so many health problems.

Keefer showed me pictures of some of the vegetation being planted. They didn’t look like trees to me – more like small, shrubby bushes. Here’s hoping they survive and grow and have the desired effects.

Keefer plans to share his experiences in Uzbekistan with Kootenay audiences in the first part of 2020, and hopes to use the presentations to raise funds to benefit those who most need it in Uzbekistan. Having seen a few of his pictures, I plan to attend a presentation to see more of them and hear more about his experiences and observations. I expect an engaging and thought-provoking event.

Keefer commented that “there are a lot of low-hanging fruit” in terms of improving practices in Uzbekistan, environmentally and otherwise. He thinks the current Uzbek president is, in effect, “a benign dictator” who has introduced several positive reforms. An article in Voice of America comments on the upcoming Uzbeck election on December 22.

About that object lesson

Will we ever learn? The problems we face today are huge. They're global and existential. How we got here can be summed up in Keefer’s comment about the irrigation system that has dried up the Aral Sea and poisoned so many people and animals: “[They] predicted it would dry up the Aral Sea, but they did it anyway.”

They may not have known in advance the full suite of unintended and deadly consequences – do we ever? — but they knew some and did it anyway.

Similarly, too often governments know that certain actions will have disastrous and irreversible consequences, either locally or for the entire planetary biosphere, yet they do them anyway. Because money. Money in the short term; in the longer term, completely out-of-proportion costs, mostly borne by the rest of us, and by the impoverishment of life in the form of species extinctions and the loss of life-supporting capacity generally.

The costs are not borne those who take the afore-mentioned money and run.

If more governments make decisions that benefit and preserve life instead of sacrificing it incrementally for unsustainable economic growth, and if they start doing that immediately, we may have a chance.

And fewer toxic deserts in our future.