Column: Floods and Sponges

When the Aztecs founded Tenochtitlán in 1325, they built it on a large island on Lake Texcoco. Its eventual 200,000-plus inhabitants relied on canals, levees, dikes, floating gardens, aqueducts and bridges for defence, transportation, flood control, drinking water and food. After the Spaniards conquered the city in 1521, they drained the lake and built Mexico City over it.

The now-sprawling metropolis, with 100 times the number of inhabitants as Tenochtitlán at its peak, is fascinating, with lively culture, complex history and diverse architecture. It’s also a mess. Water shortages, water contamination and wastewater issues add to the complications of crime, poverty and pollution. Drained and drying aquifers are causing the city to sink — almost 10 metres over the past century!

“Conquering” nature has long been the western way. Our hubris, and often our religious ideologies, have led us to believe we are above nature and have a right to subdue and control it. We let our technical abilities get ahead of our wisdom. We’re learning now that working with nature — understanding that we are part of it — is more cost-effective and efficient in the long run.

Had we designed cities with nature in mind, we’d see fewer issues around flooding, pollution and excessive heat, and we wouldn’t have to resort to expensive fixes. Flooding, especially, can hit people hard in urban areas. According to the Global Resilience Partnership, “Floods cause more damage worldwide than any other type of natural disaster and cause some of the largest economic, social and humanitarian losses” — accounting for 47 per cent of weather-related disasters and affecting 2.3 billion people over the past 20 years, 95 per cent of them in Asia.

As the world warms, it’s getting worse. Recent floods in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Nepal have affected more than 40 million people, killing more than 1,000. One-third of Bangladesh is under water. In Houston, Texas, Hurricane Harvey has killed dozens and displaced thousands, shut down oil refineries and caused explosions at chemical plants. Some say it’s one of the costliest “natural” disasters in U.S. history.

Although hurricanes and rain are natural, there’s little doubt that human-caused climate change has made matters worse. More water evaporates from warming oceans and warmer air holds more water. Climate change is also believed to have held the Houston storm in place for longer than normal, and rising sea levels contributed to greater storm surges.

A lax regulatory regime that allows developers to drain wetlands and build on flood plains has compounded Houston’s problems. The city has no zoning laws, and many wetlands and prairies — which normally absorb large amounts of water and prevent or lessen flood damage — have been drained, developed or paved over. President Donald Trump also rescinded federal flood protection standards put in place by the Obama administration and plans to repeal a law that protects wetlands. Compare Houston to Amsterdam and Rotterdam, which sit below sea level. Regulation and planning have helped the Dutch cities lower flood risk and save money.

As climate disruption accelerates in concert with still-increasing greenhouse gas emissions, people are looking for ways to protect cities from events like flooding. In China, authorities are aiming to make them more sponge-like. A Guardian article explains: “Designers will concede to the wisdom of nature to ensure water is absorbed when there’s an excess: instead of water-resistant concrete, permeable materials and green spaces will be used to soak up rainfall, and rivers and streams will be interconnected so that water can flow away from flooded areas.” As well as offering flood protection, the measures will also help prevent water shortages.

Cities worldwide have employed many of these flood-protection measures, including in the U.S. If China goes beyond its 16-city pilot project, it will be the largest-scale deployment of such combined measures ever.

Restoring natural areas costs much more than protecting them in the first place, more intense and frequent storms and floods can still overwhelm natural defences, and growing human populations will further stress resources, but restoring natural assets is a start.

Ultimately, we must work with nature to prevent and adapt to problems such as flooding, water scarcity, wildfires and climate disruption. When we work against nature, we work against ourselves.

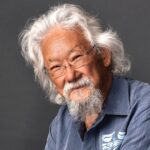

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Editor Ian Hanington. David Suzuki’s latest book is Just Cool It!: The Climate Crisis and What We Can Do (Greystone Books), co-written with Ian Hanington.

Learn more at www.davidsuzuki.org.