Opinion: Sexual assaults happen in the summertime, too. And some of us are still in the dark ages about it.

The headline above notwithstanding, people who suffer sexual assault in our region have many resources and many enlightened people available to help with all aspects of the ordeal and its aftermath. Trail FAIR is there to help, and Victims’ Assistance. And I have no reason to believe that this region’s RCMP personnel are anything but well-informed, responsive, up-to-date, and compassionate. Anyone who is sexually assaulted should report it as soon as they are able.

In general, things are beginning to look up for rape victims. More police forces and RCMP officers are undergoing specialized training. There are still a few dinosaurs sitting on court benches and acting as defence counsel for perpetrators, but recently, a judgment by Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Juliana Topolniski reversed an acquittal of a teen charged with sexual assault. The language in her ruling made it very clear that she was disappointed, to say the least, with the lower court judge’s lack of understanding of the concept of consent.

In 2014, a Federal Court judge, Robin Camp ― evidently one of the “dinosaurs” ― acquitted Scott Wagar who was accused of raping a 19-year-old woman; during the trial, the judge repeatedly referred to the complainant ― the rape victim ― as “the accused” and treated her as such, too. He asked her why she hadn’t “just kept her knees together” so she couldn’t be raped: a classic example of the victim-blaming still so common in rape proceedings.

The Gomeshi trial, now ancient history, spawned many pages of media examination of our social attitudes toward sexual violence and how our courts go about trying to determine the truth of what happened, in the face of conflicting evidence.

Scholar David Tanovich, professor of law at the University of Windsor, wrote an article on the long-established practice of “whacking” the complainant in any sexual assault case, and how the legal profession should combat it. Such whacking, Tanovich explained, includes “humiliating or prolonged cross-examination that seeks to put the complainant on trial rather than the accused.” He stated that we “need to think beyond evidence regulation to curtail the virulence of the assaults on women’s credibility in sexual assault cases.”

“Rape” was re-named in Canadian criminal law in 1983; it’s now a category of “sexual assault.” That change recognizes that there are other types of assault that are sexual in nature; that a woman doesn’t have to have a penis stuffed into her vagina or other bodily orifice, or have the courts decide whether it was stuffed far enough into the specifically approved orifice to constitute “rape”, in order to suffer the violation and trauma associated with rape.

It’s well-known that many, and probably most, sexual assaults go unreported. The reasons for not reporting are legion, but we can name a few here:

· The simple shame of admitting that one has been overpowered and diddled;

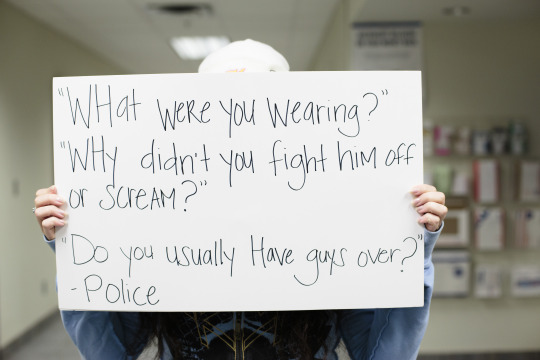

· The knowledge that some police departments will reject a claim of sexual assault if they don’t think the woman “deserves” to be believed, and that they will not use or process a rape kit;

· Reluctance to undergo the further humiliation of medical examination;

· Reluctance to face the intense and prolonged humiliation of the traditional victim-blaming attacks on her character, conduct, clothing, and other irrelevant non-issues;

· Reluctance to commit to enduring a lengthy court case during which the defence counsel will do their best to “whack” the complainant with the above-noted victim-blaming attacks and try to prove that she is lying. Or that she once lied to somebody, about something, and should not be believed about anything, ever, anymore; that nothing she says is “credible;”

· Mistaken belief that a woman cannot complain about sexual assault by her husband or live-in partner.

· And any of a range of other normal personal responses to severe trauma, such as depression and feelings of hopelessness.

Generally it is defence counsel ― the rapist’s lawyer or legal team ― who “whack the victim” by delving into a victim’s character, clothing, conduct and credibility. Too often, judges allow this. Too often, when they do these things, they rely on invalid stereotypes, prejudices and assumptions that have already been rejected by legislation and case law from other courts. In doing so, those defence counsel tend to re-animate wrong ideas that ought to have been killed off long ago ― zombie ideas; dead, but still out there doing harm. Let’s see if readers recognize ― or even, at some level, share ― a few of these rejected assumptions. Let’s call them what they are: stupid. Bear in mind that this is not a comprehensive list:

Stupid Assumption #1: “A woman who has had sex at all before the rape cannot be believed. She lost her honesty along with her virginity.”

Stupid Assumption #2: “A woman who has had sex without being married would never refuse to have more sex, with anyone, at any time, for any reason; (OR, she has no right to refuse);”

Stupid Assumption# 3: “A woman who has been raped must have been asking for it. Her clothing wasn’t sufficiently concealing, or drab, or otherwise uninviting; OR she did some other thing that made her fair game for rapists, such as dancing suggestively or being drunk, or letting someone kiss her.”

Stupid Assumption #4: “A woman who doesn’t rush immediately from the scene of the assault to report it must be lying if she reports it later on.”

Stupid Assumption #5: “She didn’t fight back hard enough to prevent the attack, or scream loudly enough, therefore she must have consented to it.”

Stupid Assumption #6: “A woman who claims not to be able to recall details such as the exact time of the assault, or what make of car the rapist drove, or what colour his eyes/hair/ shirt were, must be inventing the whole thing.”

Stupid Assumption #7: “Women are responsible for preventing assaults by men.”

Stupid Assumption #8: “Rape or other sexual assault just isn’t a serious enough crime to take very seriously.”

A number of Canadian legal scholars have been examining these assumptions and how they are still used against the victims of sexual assault, despite changes in legislation designed to prevent that and despite rulings of the Supreme Court of Canada.

One such ruling in 1999, in R. v. Ewanchuk, clarified that “No defence of implied consent to sexual assault exists in Canadian law.” The court went on to state that “To be legally effective, consent must be freely given.” That means that an apparent consent obtained by means of threats, force, the exercise of authority, or other forms of duress is not freely given and is not valid consent.

In 1992, Canada enacted what is known as the “rape-shield” law. It restricts questioning of a rape victim on her previous sexual history. In 2000, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) upheld the constitutionality of the rape-shield law in the case against one Andrew Scott Darrach, accused of sexually assaulting his ex-girlfriend. Darrach and his lawyer seemed to think, since she was once his girlfriend and had consented to sex with the accused at that earlier time, that whatever Darrach did could not be sexual assault.

Recently, in R. v. Saeed, the SCC ruled that police can take penile swabs from a suspect to check for the presence of the complainant’s DNA without obtaining a warrant in advance. In its ruling, the court set out strict rules to protect the dignity of the accused and the integrity of the process.

Things are looking up because appeals courts including the SCC have been striking down judgments of trial judges who rely on the stupid assumptions listed above in their decisions. Unfortunately, victims of sexual assault still cannot rely on having trial judges, or juries, who do not hold any or all of those stupid assumptions dear in their personal collection of unreasonable prejudices.

Things are improving, but we still have a long way to go.