Hot, hungry and hostile: Dyer's dire prediction for our global future

By Michelle Martin

“It’s going to get depressing at the middle of this talk, and it will end up a little more cheerful. Be patient and don’t cry.”

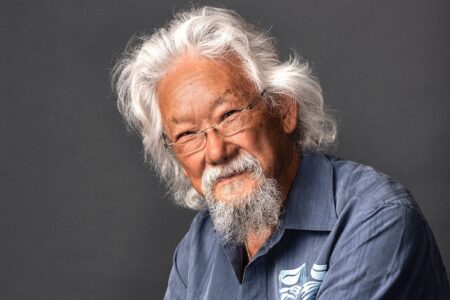

With that cautionary note, Gwynne Dyer began his 2011 Power Smart Forum keynote address: Hot, Hungry & Hostile: The Geopolitics of a Warming World.

The talk, which is available via an archived webcast, turned out to be as engaging to the 700-member audience on hand as it was disturbing.

Climate change & the Pentagon

The renowned social commentator and 2010 Order of Canada recipient admitted early in his keynote at the Vancouver Convention Centre that, up until he took a trip to Washington three years ago, he hadn’t worried much about climate change.

It was on that trip that a friend in the American Forces mentioned the Pentagon’s interest in global warming, and how the military may get involved.

Dyer discovered the American Forces weren’t alone in this interest, and he launched an 18-month investigation, where he interviewed more than 100 people in a dozen countries, including scientists, academics, military personnel and think-tank staff. He shared his conclusions from that study with the Forum audience.

The earth is warming much faster than we think

When it comes to the rate of global warming, the numbers we are using do not conform to what we are observing, asserted Dyer.

There’s up to a 10-year lag time between data collection, analysis, publication in peer-reviewed journals and the analysis of multiple study findings by leading agencies, whose findings are often referenced years after their reports are released.

For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has projected that the sea level will rise by about half a metre by the end of the century. But dyke experts in the Netherlands told Dyer that they were working with a metre-and-a-half prediction.

“That’s simply an extrapolation of the annual rate of risk we’re experiencing at the moment — and that’s without the Greenland ice cap melting,” said Dyer.

His research suggested that, based on current behaviour, in 50 years the earth would see an average higher global temperature of four degrees Celsius, which equates to seven degrees inland. In Canada, that would impact the provinces from Alberta to Quebec.

Problems are almost always related to food shortages

Military concerns relate to the global food supply and how it impacts different areas of the globe differently.

“Basically, the closer to the equator you are, the deeper the trouble you’re in. Even a two-degree rise would push most tropical crops beyond the temperature tolerance range,” said Dyer. “There’s always enough to buy food if you’ve got enough money, but the vast majority of people who cannot pay the high prices of food pay a different price instead.”

There’s also a big gap in responsibility for global warming. According to Dyer, China and India are well aware that 80 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) of human origin were produced by developing countries — in the process of increasing their wealth — burning fossil fuels over the last two centuries.

“They’re already resentful about it — and they’re not even starving yet,” he said, recalling a study in India that predicted a two-degree rise in temperature would result in crop losses of 25 per cent in India and 38 per cent in China.

What does the military foresee as a result? Massive numbers of refugees, failed states and international wars:

A mass influx of refugees north could strain international relations. Dyer described a scenario in which the U.S. would close the Mexican border through force, akin to the Iron Curtain.

States would fail as governments, unable to feed their people, lost their right to rule. Dyer described widespread pirating and terrorism akin to Somalia’s today.

International wars could emerge between countries sharing the same river system. Dyer used the example of the growing tension between the upstream and downstream countries that border the Nile River.

A global solution is possible, if it’s done soon

Dyer said that the future world that militaries are bracing for is not a cooperative or friendly one capable of making global deals.

“We could now negotiate a global deal that would stop emissions in a reasonable length of time,” he said. “Political possibilities for solving the problem diminish as the problem grows.”

Today, he says, a deal to solve the problem would have to involve developed countries — like Canada — cutting 30 per cent emissions in 10 years. Meanwhile, rapidly-developing industrializing countries in the south would have to immediately cap their emissions.

From there, industrialized countries would need to support the developing world’s further growth out of poverty by supporting green energy, which comes at a higher cost than coal.

“The problem — why they can’t sign the deal — is politics. Nobody here knows the history or understands the historical injustice of us taking up all the room in the atmosphere before developing countries even started to industrialize,” said Dyer.

There’s a point of no return

By most scientific estimates, Dyer said, the point of no return is a temperature rise of two degrees: that’s when GHGs from natural sources, such as melting permafrost, become a problem.

Meanwhile, as oceans warm, they lose their ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

“We may be trapped on an up-bound escalator with no way off — this is what gives the scientists nightmares,” he said. “On all present evidence, we’re going to go through it in about 15 years; and we’ll be committed to it by 2020.”

Do we have a parachute?

While the long-term solution must be quelling GHGs, Dyer noted a shorter term solution to avoid the two-degree point of no return.

Geo-engineering, or solar radiation management, may offer a way to cut out incoming sunlight by one or two per cent by, for example, putting sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere.

“People are starting to say that we better be ready to do it or understand why we mustn’t, but we can’t go past the point of no return,” he said. “This is desperation stuff and it’s only temporary, but it may help us win some more time.”

Conservation also plays the vital role of buying us more time. But there’s not much time — Dyer predicts that even if we don’t hit the point of return, our continued use of fossil fuels will get us very close.

“I think we can do it, but it’s very frightening,” he said.

- Watch the archived webcast to see Dyer in action.