Column: Concurrent crises expose systemic flaws

The coronavirus spreading COVID-19 around the globe isn’t the first disease microbe suspected to have jumped from other animals to humans, nor will it be the last. That we know to a large extent why so many diseases are making that leap should help us resolve the problem.

Dealing with a swiftly spreading illness with many unknown consequences is clearly the top priority now. We’re fortunate in Canada to have a medical system somewhat equipped to handle such crises, leaders who rely on evidence and compassion, and some measures to protect workers from lost time and wages.

Scientists say we can expect more disease outbreaks as the climate warms, although research into how global heating affects human-to-human spread is still in early stages. The novel coronavirus is thought to have been transmitted to humans from animals, possibly bats. Climate change, habitat destruction, growing human populations and wild-game markets put us in closer contact with creatures that can spread disease, and make them more susceptible to disease outbreaks. We’ve also seen disease-carrying ticks and mosquitoes move into areas where longer, colder winters once kept them in check.

Diseases can also jump to humans from domesticated animals, as we’ve seen in Canada with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease moving from cattle to people, and avian flu from birds.

Our constant-growth mindset, which assumes production and human populations will continue to expand, also means many more of us are living in closer quarters, often flying around the world, which contributes to infectious disease spread.

We have a lot to learn still, but COVID-19 can teach us ways to address a crisis with many unknowns, whether it’s a disease pandemic, a rapidly heating planet or accelerating biodiversity loss.

We’ve seen that decisive action can substantially reduce health risks and contagion, as well as emissions and the activities that cause them — and that by heeding the advice of scientists and experts, business and government leaders can make an immediate difference, with public support.

Curtailment of flights, cruise ship tours, major public events and some industrial activity has led to a dramatic drop in greenhouse gas emissions — along with declines in economic activity. A European study found 11,000 fewer people died from pollution-related causes over one month than before the pandemic shutdown, as levels of dangerous pollutants like nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter declined. Air pollution has also been shown to exacerbate COVID-19’s effects and outcomes.

But, as UN secretary general António Guterres cautioned, “We will not fight climate change with a virus.” He pointed out that “both require a determined response. Both must be defeated.”

If people have responded with much more immediacy and urgency to the pandemic than the climate crisis, it’s possibly because it seems more present and resolvable. Although the impacts of climate disruption are accelerating daily, many don’t see it as a direct threat. Those who understand that it’s immediate and worsening often feel there’s little to be done, whereas the personal and institutional actions to limit pandemic spread seem relatively simple, timely and effective.

That the world is facing several crises at once is challenging, but maybe it offers an opportunity to reset. Along with the coronavirus and climate disruption, oil prices have also plummeted, partly because of a dispute between Russia and Saudi Arabia. An oil-dependent economy like Canada’s can’t escape the impacts — especially in Alberta where successive governments have pinned their hopes on bitumen and gas rather than adequately diversifying.

We must continue to take precautions to avoid catching and spreading COVID-19, like washing hands regularly, avoiding touching our faces and practising distancing. Working to ensure that our medical system is maintained and strengthened is also important.

As a society, we must learn to slow down and stop consuming so much. We must get serious about the many threats to human health and well-being, including climate disruption, loss of plant and animal species and new diseases. Making the world safer means taking immediate precautions and measures, but it also means looking into ways to alter our behaviours to lessen our destructive impacts on air, water, land, climate and biodiversity. It means conserving and using energy more efficiently and shifting to renewable sources, and preserving and restoring wild spaces.

Be healthy. Be safe.

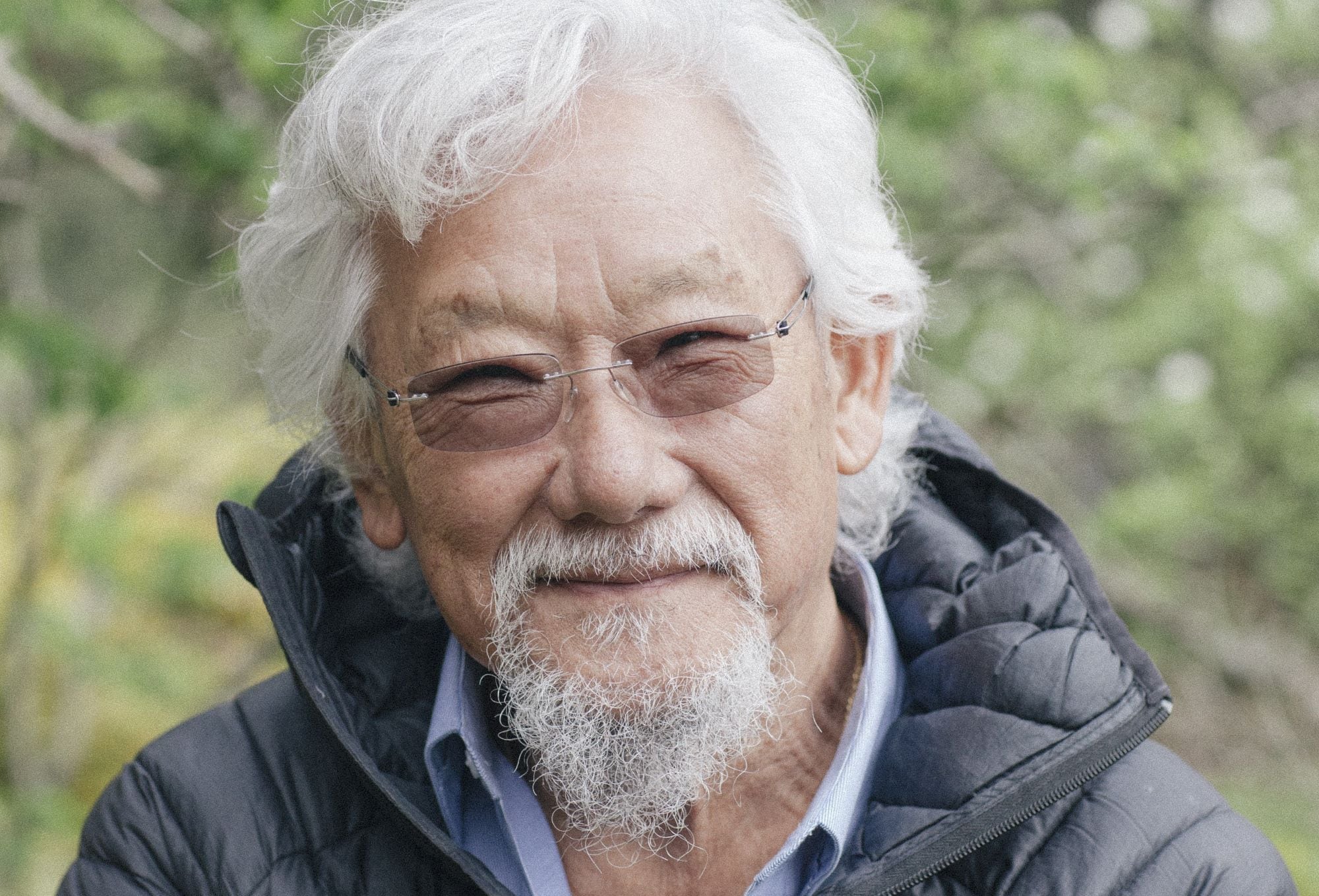

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.