Op/Ed: Canada doesn't protect whistleblowers, and they're at serious risk.

By Paloma Raggo, for The Conversation

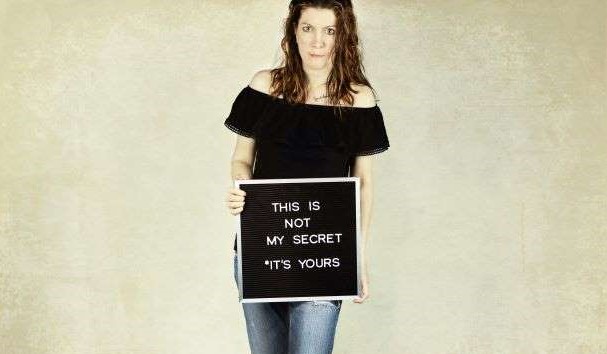

Whistleblowers put their careers, and sometimes their safety, on the line to protect democratic ideals and the public interest.

Canada, like its southern neighbour, is not immune to whistleblowing controversies at the highest levels of government. Would a whistleblower be protected in Canada if faced with a situation similar to the White House whistleblower’s? Not so much.

There are countless examples of Canadian public officials who have suffered reprisals such as having their personal information disclosed, being forced into early retirement, being fired, threatened and even bankrupted after going public with allegations of wrongdoing.

For example, in 1998, three Health Canada scientists revealed they were being pressured to approve veterinary drugs that would get into the food supply without the legally required evidence of human safety. Their revelations ultimately led to a ban on bovine growth hormone. However, after blowing the whistle, they were fired for “insubordination.”

During the 2004 sponsorship scandal, a Public Works procurement officer refused to sign off on advertising contracts that he felt broke the rules of normal procurement. He was effectively fired.

This led to the eventual revelation that advertising contracts worth millions from the federal sponsorship program were being illegally directed to government-friendly firms.

In 2013, a senior lawyer with the Department of Justice challenged his own department in court for allowing laws to be enacted that would likely infringe upon the Canadian Charter and Bill of Rights. He was suspended without pay and eventually took early retirement.

Not clearcut

Whistleblowing cases are not always clearcut. The Canadian legislation aimed at protecting whistleblowers in Canada, which provincial laws are modelled on, is the Public Servant Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA). It adopts a narrow definition of whistleblower, protecting only certain federal employees.

Some argue that a whistleblower can be anyone who has knowledge of wrongdoing by an organization. Whistleblowers are often accused of being disgruntled, misguided or otherwise flawed employees.

For instance, in 2016, a Saskatchewan nurse who was home on maternity leave criticized on Facebook the care home where her grandfather was a patient. As a result, the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association disciplined Carolyn Strom for professional misconduct and bringing the profession into disrepute, and fined her $26,000.

The B.C. Civil Liberties Association has expressed concern that the ruling will discourage health-care workers from discussing problems they encounter, even in private forums. A lawyer for the nurse’s association argued that Strom “should have taken internal measures instead of speaking publicly and identifying herself as a nurse.”

More recently, Jody Wilson-Raybould, former justice minister and attorney general, alleged that she was wrongfully pressured by the Prime Minister’s Office to intervene in the prosecution of SNC-Lavalin for overseas bribery in favour of a deferred prosecution agreement.

The fact that she alleged wrongdoing against her superiors put her in the middle of a political storm.

Ineffective legislation

The PSDPA act has been criticized as ineffective by free speech advocates. It has a restrictive definition of who is a whistleblower, and does not cover all the people who may have knowledge of an organization’s affairs.

The act provides the option for employees to use the internal disclosure process — contacting a supervisor, or “senior disclosure officer” or directly to the Public Service Integrity Commissioner (PSIC). The in-house strategy has a chilling effect because potential whistleblowers might need to air their grievances with the very managers they’re experiencing problems with.

Opting to go to the Public Service Integrity Commissioner often doesn’t help, because the commissioner can refuse to deal with any disclosure — either in terms of wrongdoing or reprisal.

Whistleblowers aren’t permitted to air their grievances publicly, except where there is urgent threat to health or safety. They are not permitted to go to members of Parliament or the courts for help, and they’re blocked by the commissioner from access to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal in most cases.

This asymmetrical system also puts the onus on the whistleblower to prove the reprisals they face for coming forward are actually reprisals, acknowledged by experts as a near-impossible task.

Failing spectacularly

Despite the importance of whistleblowing as a fundamental check on power in democratic societies, Canada fails spectacularly in the area of whistleblower protection laws.

In June 2017, the government’s Operations and Estimates Committee, made up of MPs from all parties, submitted a unanimous report to the government lamenting restrictions and lack of clarity in the Public Servants Disclosure Act and recommending amendments.

The government response came a few months later and made clear there would be no legislative changes. Whistleblowing expert Tom Devine, from the U.S. Government Accountability Project, noted at the 2019 International Whistleblowing Research Conference that Canada’s whistleblowing act did not contain even one of the 20 elements considered “best practice” for whistleblowing protection legislation.

Pamela Forward, president of the Whistleblowing Canada Research Society, a leading think tank on the issue noted:

“Canada’s treatment of whistleblowers should be of imminent concern … because a whistleblower in a situation like the one currently unfolding in the U.S. would not enjoy a similar level of protection in Canada.”

Whistleblowers can play a crucial role when democratic institutions begin to disintegrate by providing a check on abuses of power and accountability at all levels of government.

Whistleblowers protect us. But who protects them?

Author Paloma Raggo is an Assistant Professor of Philanthropy and Non-profit Leadership at Carleton University. She receives funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She is a board member of Whistleblowing Canada Research Society.