COLUMN: Nature Deficit

Renowned biologist Edward O. Wilson says to protect nature, people must regain their innate love for it. That means spending time in nature. While the concepts in Wilson’s book Biophilia have gained widespread acceptance since its publication more than 30 years ago, we’re still facing serious problems based on a lack of understanding of and attention to the natural environment.

The only nature connection some political representatives and media influencers have appears to be time on the golf course (hardly natural) or excursions into wild areas to kill animals for trophies. Many people, especially in Western societies, are spending less time in nature than ever before.

A Nature Conservancy of Canada survey found almost 90 per cent of respondents “feel happier, healthier and more productive when they are connected to nature,” but “74 per cent say that it is simply easier to spend time indoors and 66 per cent say they spend less time in nature today than in their youth.”

Young people are also spending increasingly more time glued to electronic devices and less time in green spaces.

The personal benefits of spending time in nature are well known. Research shows time outdoors can reduce stress and attention deficit disorder; boost immunity, energy levels and creativity; increase curiosity and problem-solving ability; improve physical fitness and co-ordination; and even reduce the likelihood of developing near-sightedness! But as screen time replaces green time, humans are increasingly suffering from what author Richard Louv calls “nature deficit disorder.”

An even bigger issue is that many people making decisions that profoundly affect all our lives have so little connection to nature that they fail to understand the consequences of their policies and actions on the natural systems on which our health, well-being and survival depend. As Wilson told PBS Nova, “I doubt that most people with short-term thinking love the natural world enough to save it.” What could be more short-term thinking than rushing to exploit as many fossil fuel resources as possible before cleaner energy sources and the realities of global warming make them economically unviable?

Ever-growing human populations, consumer-driven economics, short political cycles and narrow thinking have fuelled an alarming rate of environmental degradation and destruction. The Nature Conservancy survey found “more than 80 per cent of Canadians worry that accessible natural areas will not be there for future generations to enjoy.”

It’s a legitimate fear. We base many of our activities on an incomplete understanding of natural systems. Industry — with government approval — clear cuts a forest and thinks replanting it with a single species will make up for the loss of a complex, diverse ecosystem. Not long ago, fungi were classified as plants, but in the mid-20th century, scientists discovered they’re closer to animals than plants but different enough from both that they merited their own classification. Even more recently, we have begun to learn about their crucial role in forest ecology.

It’s only recently that science has started to catch up on what Indigenous cultures have known for millennia: that everything in nature, including us, is connected. Short-term thinking justifies putting a salmon population at risk to get more money for bitumen on international markets. But when the salmon are gone, so too are the whales, bears and eagles that eat them, and the rain forests their nitrogen-rich carcasses fertilize as they complete the cycle of life and death from the oceans to spawning grounds.

If you spend time in nature, your senses open to its intricacies and beauty, from the complexity of a leaf or dragonfly to the majesty of an old growth forest. You start to see how many of our priorities are petty and limited. It’s also easier to understand how affecting one part of an ecosystem affects the entire ecosystem and the surrounding environment.

It’s tragic that so many “leaders” fail to understand their connection with nature or appreciate its importance and intricate beauty. Many would be happier and healthier if they spent more time immersing themselves in nature. They’d also make better decisions.

Understanding that we’re part of something much bigger than ourselves is a necessary step to healing this wonderful world that we have treated so badly. So, get outside — for your own sake and the sake of the planet.

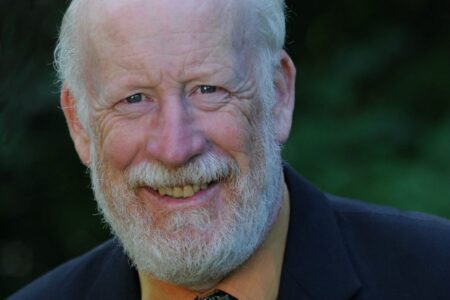

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Editor Ian Hanington.

Learn more at www.davidsuzuki.org.

Renowned biologist Edward O. Wilson says to protect nature, people must regain their innate love for it. That means spending time in nature. While the concepts in Wilson’s book Biophilia have gained widespread acceptance since its publication more than 30 years ago, we’re still facing serious problems based on a lack of understanding of and attention to the natural environment.

The only nature connection some political representatives and media influencers have appears to be time on the golf course (hardly natural) or excursions into wild areas to kill animals for trophies. Many people, especially in Western societies, are spending less time in nature than ever before.

A Nature Conservancy of Canada survey found almost 90 per cent of respondents “feel happier, healthier and more productive when they are connected to nature,” but “74 per cent say that it is simply easier to spend time indoors and 66 per cent say they spend less time in nature today than in their youth.”

Young people are also spending increasingly more time glued to electronic devices and less time in green spaces.

The personal benefits of spending time in nature are well known. Research shows time outdoors can reduce stress and attention deficit disorder; boost immunity, energy levels and creativity; increase curiosity and problem-solving ability; improve physical fitness and co-ordination; and even reduce the likelihood of developing near-sightedness! But as screen time replaces green time, humans are increasingly suffering from what author Richard Louv calls “nature deficit disorder.”

An even bigger issue is that many people making decisions that profoundly affect all our lives have so little connection to nature that they fail to understand the consequences of their policies and actions on the natural systems on which our health, well-being and survival depend. As Wilson told PBS Nova, “I doubt that most people with short-term thinking love the natural world enough to save it.” What could be more short-term thinking than rushing to exploit as many fossil fuel resources as possible before cleaner energy sources and the realities of global warming make them economically unviable?

Ever-growing human populations, consumer-driven economics, short political cycles and narrow thinking have fuelled an alarming rate of environmental degradation and destruction. The Nature Conservancy survey found “more than 80 per cent of Canadians worry that accessible natural areas will not be there for future generations to enjoy.”

It’s a legitimate fear. We base many of our activities on an incomplete understanding of natural systems. Industry — with government approval — clear cuts a forest and thinks replanting it with a single species will make up for the loss of a complex, diverse ecosystem. Not long ago, fungi were classified as plants, but in the mid-20th century, scientists discovered they’re closer to animals than plants but different enough from both that they merited their own classification. Even more recently, we have begun to learn about their crucial role in forest ecology.

It’s only recently that science has started to catch up on what Indigenous cultures have known for millennia: that everything in nature, including us, is connected. Short-term thinking justifies putting a salmon population at risk to get more money for bitumen on international markets. But when the salmon are gone, so too are the whales, bears and eagles that eat them, and the rain forests their nitrogen-rich carcasses fertilize as they complete the cycle of life and death from the oceans to spawning grounds.

If you spend time in nature, your senses open to its intricacies and beauty, from the complexity of a leaf or dragonfly to the majesty of an old growth forest. You start to see how many of our priorities are petty and limited. It’s also easier to understand how affecting one part of an ecosystem affects the entire ecosystem and the surrounding environment.

It’s tragic that so many “leaders” fail to understand their connection with nature or appreciate its importance and intricate beauty. Many would be happier and healthier if they spent more time immersing themselves in nature. They’d also make better decisions.

Understanding that we’re part of something much bigger than ourselves is a necessary step to healing this wonderful world that we have treated so badly. So, get outside — for your own sake and the sake of the planet.

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Editor Ian Hanington.

Learn more at www.davidsuzuki.org.