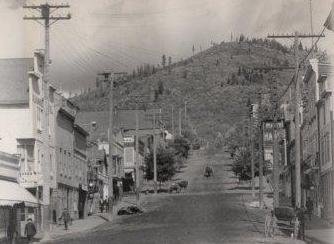

LEGENDS AND TALES OF THE MOUNTAIN KINGDOM: Patsy Clark & the electrification of Rossland

In the heart of Spokane’s historic Browne’s Addition, there is a fabulous mansion that is now part law office and part catering venue for weddings and such events. Featuring architecture inspired by Spanish and Moorish influences, a rounded tower, and was partially constructed from sandstone imported from Italy.

It belonged to one Patrick Clark, commonly called Patsy. A ridiculously wealthy mining magnate of Irish descent, Patsy was a well-known figure on the mining scene in the States and in the upper crust of Spokane’s society, but he was also a very important figure in Rossland’s history for a couple of different reasons.

Born on St. Patrick’s Day, 1852 in Ireland, Patsy (an unfortunate nickname, if you ask me), emigrated to the States when he was 18 years old, and upon arriving on US soil in New York, he travelled west to California where he set out to learn the mining business. In 1876, he meandered off to Montana, where he became foreman of the Alice Mine, which was owned by fellow Irishman and so-called “Copper King” Marcus Daly. Interestingly enough, Patsy spent some time with the US army in Montana and participated in the Nez Perce War of 1877, where he took part in the Battle of Big Hole. After that, he went on to open and be the foreman of several large mining operations in Montana, Virginia, and eventually Idaho, after seeking new opportunities in Spokane.

In 1893, after the promising finds at the Le Roi Mine, the War Eagle property was starting to look pretty interesting, though at first nothing seemed to pan out. But in 1894, Patsy Clark arrived on the scene and took another look. What he saw made him want to develop the site further.

According to Jeremy Mouat’s Roaring Days, “[Patsy] soon discovered that earlier developers of the War Eagle had lost sight of the ore. Redirecting the tunnel, he struck the ore after driving for 70 feet.” In December 1894, Patsy signed a contract with a smelting company in Montana to provide 1000 tonnes a month of ore from the War Eagle Mine. It was an unprecedented contract, and, again quoting Mouat, “The War Eagle began paying dividends on 1 February 1895. Prospectors and miners flocked to Rossland, its population rising swiftly from 75 to 3000.”

Historian and oft-quoted Harold Kingsmill, author of The First History of Rossland, credited Patsy alone as the reason for the prosperity and fame of early Rossland and Trail Creek Landing as the new mining mecca. The War Eagle itself would become one of Rossland’s three big mines, along with the Le Roi and Centre Star.

This is the first reason why Patsy is important. The second reason is that he also was a key figure in the electrification of Rossland.

Obviously, Rossland was still a muddy mining town back then with not many luxuries at all, certainly no furnaces, no running hot water, and not even electricity. Patsy Clark, however, had big ideas–though to be fair, his electricity scheme had more to do with making his mine more efficient and productive, but it was a nice side effect that some of the town benefited from his plans.

In 1895, after the War Eagle was up and running, Pasty and a partner inked a deal with Washington Power and Light owners to set up a subsidiary of that company called the Rossland Light and Water Company. According to the Crowsnest.ca website, the bought a “a “700-lamp capacity” bi-polar direct current Edison generator. They connected this to a an old steam engine – not a train, but a stationary one – that was houses in a building located at the corner of Thompson Avenue and Washington Street.

Whatever electricity was left over after lighting the War Eagle, they sold to Rosslanders. Crowsnest.ca goes on to say, “On January 7th of 1896 the switches were thrown and a few dozen low-wattage light bulbs glowed to life in stores along Columbia Avenue, Spokane Street and Sourdough Alley.” It must have seemed like magic!

As this was going on, Patsy’s new company also hatched a plan to bring water to the community, again initially for mining reasons. The water, coming to town via a pipeline built from a reservoir at Stoney Creek, was meant to run a “pelton wheel generating set” that was there to augment the output of the Edison generator. Eventually, the good old Edison was deemed inadequate for everyone’s needs, and it was replaced with a “pair of 1500 horsepower Corliss engines and matching 16-candlepower generators. These served until West Kootenay Power began supplying electricity in 1898.”

And speaking of West Kootenay Power, it was previously called the West Kootenay Power and Light Company, and was incorporated in 1987. Its first big project was a hydroelectric power station near where the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers joined, and then to build a huge transmission line between the station and Rossland. Heritagebcstops.com says, “This resulted in what was then the longest and highest voltage transmission line in the world. At 20,000 volts, the line would set new Canadian transmission records and would be the first in the world through alpine terrain.” Patsy and company must have been thrilled to replace their rather primitive little operation with something so grand.

The electricity came from the hydro station at Bonnington Falls, and the “Bonnington to Rossland project took just under a year, and on July 15, 1898, 500 lights were shining in Rossland.” I can only imagine how miraculous this would have seemed to the few thousand people now living in Rossland who had previously been mostly living in the dark and relying on candles and lanterns.

We now take electricity for granted. And Rossland in its rugged, mountainous location must have been a bit of a formidable place to bring electricity to back in the late 1890s. But it was all part of the evolution of a mining camp turned boomtown, and it happened around the same time Rossland was starting to organize itself into a proper little city, with streets, and a mayor, and other infrastructure. And it all started with an Irishman named Patsy Clark who had a vision and a keen eye for potential. He died in 1915 after spearheading many more mining projects.

Sources

1. http://www.crowsnest-highway.ca

2. http://www.heritagebcstops.com/crowsnest-tour/west-kootenay-power

3. http://www.legendsofamerica.com/wa-patsyclark.html

4. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patsy_Clark_Mansion

5. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcus_Daly

6. http://www.mailtribune.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20100829/NEWS/8290324/-1/LIFE11

7. The Montreal Gazette, April 13, 1899

8. Roaring Days: Rossland’s Mines and the History of British Columbia, by Jeremy Mouat