TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE MOUNTAIN KINGDOM: High stakes negotiations--Rossland style

The fate of a smelter decided by a poker game? Late night sleigh ride dashes up the mountain to have a chum intervene in your smelter negotiations at a chi-chi, assuredly cigar smoke-filled local club? Yes! The fate of the future Cominco depended on it!

In December 2010, I worte an article about the train race in Rossland between two men, Augustus Heinze and Daniel Corbin. I mentioned that both Heinze and Corbin had smelting interests as well: Heinze owned the British Columbia Mining and Smelting Company and its smelting operation at Trail Creek Landing. Corbin, not to be outdone, started up the smelter at Northport after building a railway between that town and Rossland. But the times they were a’changing, and Canada’s national railway company, the CPR, had its eye on Heinze’s assets, and Corbin, ever the opportunist, knew that Heinze’s contract with the LeRoi Mine to smelt ore was nearly up and he had a better deal to offer and the manipulativeness to pull it off.

Media reports had started rumours that the CPR was wanting to get into the metal game and start up a smelter at Blueberry Creek. Heinze sensed he was about to be pushed out completely, so he took a gamble – literally. And in the aftermath, it was left to two high-profile Rossland residents to broker a deal at a local club that would see Heinze ousted from the area altogether.

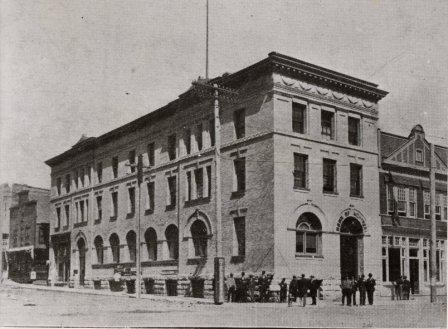

If you haven’t heard of J.S.C. Fraser, AKA James Sutherland Chisholm Fraser, that’s not surprising. Though most sources tout him as a large figure in the early community of Rossland, for some reason, Harold Kingsmill, author of First History of Rossland, B.C omits him from the work altogether. Fraser was the first manager of the Bank of Montreal in Rossland in 1896, and had had a long career with that company before coming to Rossland. He’d been posted all over Canada. He would have had his digs in the upper levels of the BoM building.

Fraser was the first president of the Rossland Board of Trade, and he had an interest in athletics. He was the president of the Rossland Curling and Skating Rink Association and the Kootenay Curling Association. One source calls him a “foremost citizen of the community.” But he is perhaps best known for his role in the Heinze-CPR-smelter deal, which went down in the Rossland Club, of which he was the the first president.

The other character in this small but fabled drama was a guy by the name of William Hull Aldridge. He was a mining and metallurgical engineer from New York and he was employed by the CPR. He was “in charge of all the mining and metallurgical work of the railroad, and soon was among the foremost mining men of the American Continent”. He was also a resident of Rossland, married to a Rosslander and raising three children with her, and he was a member of the Rossland Club, to boot.

The crux of the matter was this: Fritz Heinze wanted out of the area after Corbin had managed to lure the LeRoi Mine’s managers to contract with him and his company to smelt their ore in Northport. Heinze couldn’t compete with Corbin’s prices. Also, the CPR was actively seeking to increase its holdings in the Kootenays and they had their eye on Heinze’s C&W Railroad, plus there were those pesky rumours that the CPR might be into building its own smelter in the area.

The writing was on the wall: Heinze wanted to sell.

In late 1897 the CPR offered to buy Heinze’s railroad, but he turned down their offer, saying he’d only sell if they bought his whole Canadian operation–including the smelter–for $2 million. Imagine the guffaws of CRP big wigs. Imagine Heinze’s discomfort when the CPR sent in Aldridge to assess the value of the smelter, only to have him find that it wasn’t worth anywhere near what Heinze wanted for it. It had been nearly non-functioning since the ore was now going to Corbin’s Northport smelter for processing. Heavy negotiations ensued.

Heinze tried to pull a fast one on the CPR by submitting an offer that didn’t include the railway–but the CPR saw right through it and got fed up. They sent in Aldridge and put him in charge of all the negotiations.

Things came to a head on February 11, 1897 when the bargaining fizzled over a mere $300,000. Though “Heinze and Aldridge evidently enjoyed their bargaining,” and indeed, the two most likely knew each other, small community as it was, Heinze all of a sudden offered that they settle the quibbling with a hand of poker. We can just imagine how that would go over with Aldridge. Naturally, he declined, and instead, perhaps prompted by overtiredness and maybe by a bit of booze, the two men decided on a whim to go to Rossland in the middle of the night. In a sleigh.

It was a bit of a hair-brained idea, but no more so than the poker idea Heinze came up with. It’s entirely possible that Aldridge said something like, “You know, Fritz, I know this guy in Rossland, upstanding man, manager of the Bank of Montreal. In fact, we’re great friends; we belong to the same club! In fact, he’s the prez. He’s good at negotiating stuff. Let’s get in a horsedrawn sleigh, sail up the mountain to Rossland, damn the frigid weather, and get him to help us settle this once and for all!”

And what could Fritz do but agree, since the poker idea was out.

And so they did it. They hired a sleigh and flew up to Rossland in it in the middle of the night and pounded on Fraser’s door at his digs in the Bank of Montreal. Quite possibly clad in a nightshirt and one of those long, pointy sleeping caps with a pompom on it, Fraser opened the door and was subsequently “dragged…over to the premises of the old Rossland Club” where he proceeded to arbitrate the deal between Heinze and the CPR.

I imagine cigars and whiskey and a dimly lit room and a lot of smoke hanging in the palpable air. I imaging that it was relatively good natured; Heinze knew he was done for and it was only a matter of a few bucks here and there. And by a few, I mean around $800,000: $600,000 for the railroad and $200,000 for the smelter. Heinze would keep a large swath of land, his real estate in Trail, some mining properties, and a couple of other incidentals. Just before breakfast time, the deal was sealed, and it was finalized March 1. Everyone went home happy.

Heinze would eventually sell all of his property north of the border, and leave the area forever.

The CPR renamed Heinze’s operations the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, and Aldridge was put in charge of turning it into a first class operation. Fraser left Rossland by 1905, settled in Victoria, and died there in 1914.

It’s an almost movie-worthy story. Or perhaps sitcom-worthy. But this is how a deal that changed the landscape of the area was brokered: with drama, with humour, with flair, and in a smoky back room in downtown Rossland.

Sources:

1. www.crowsnest-highway.ca

2. http://discoveringthekootenays.ca/gb.html

3. http://user.xmission.com/~search/aldridgew.htm

4. “First History of Rossland, B.C : with sketches of some of its prominent citizens, firms and corporations”, by Harold Kingsmill

5. http://memorybc.ca/j-s-c-fraser-fonds;rad

6.http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/r-e-r-edward-gosnell/a-history-british-columbia-hci/page-42-a-history-british-columbia-hci.shtml