Financial ties bind medical societies to drug and device makers

By Charles Ornstein and Tracy Weber

SAN FRANCISCO — From the time they arrived to the moment they laid their heads on hotel pillows, the thousands of cardiologists attending this week’s Heart Rhythm Society conference have been bombarded with pitches for drugs and medical devices.

St. Jude Medical adorns every hotel key card. Medtronic ads are splashed on buses, banners and the stairs underfoot. Logos splay across shuttle bus headrests, carpets and cellphone-charging stations.

At night, a drug firm gets the last word: A promo for the heart drug Multaq stood on each doctor’s nightstand Wednesday.

Who arranged this commercial barrage? The society itself, which sold access to its members and their purchasing power.

Last year’s four-day event brought in more than $5 million, including money for exhibit booths the size of mansions and company-sponsored events. This year, there are even more “promotional opportunities,” as the society describes them.

Concerns about the influence of industry money have prompted universities such as Stanford and the University of Colorado-Denver to ban drug sales representatives from the halls of their hospitals and bar doctors from paid promotional speaking.

Yet, one area of medicine still welcomes the largesse: societies that represent specialists. It’s a relationship largely hidden from public view, said David Rothman, who studies conflicts of interest in medicine as director of the Center on Medicine as a Profession at Columbia University.

Professional groups such as the Heart Rhythm Society are a logical target for the makers of drugs and medical devices. They set national guidelines for patient treatments, lobby Congress about Medicare reimbursement issues, research funding and disease awareness, and are important sources of treatment information for the public.

Dozens of such groups nationwide encompass every medical specialty from orthopedics to hypertension.

“What you’re exploring here is the subtle ways in which the companies and professional societies become partners and — wittingly or unwittingly — physicians become agents on behalf of the interests of the sponsoring company,” said Dr. Steven Nissen, chair of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“It has a not very subtle effect on medicine,” said Nissen, an expert on the impact of industry money.

‘This is our business’

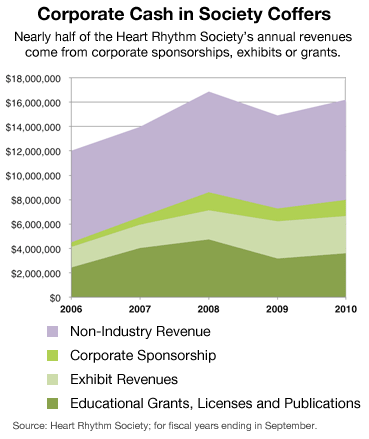

Nearly half the $16 million the heart society collected in 2010 came from makers of drugs, catheters and defibrillators used to control abnormal heart rhythms, the group’s website disclosed.

Officials of the Heart Rhythm Society say industry money does not buy influence and is essential to developing new treatments. Still, on Thursday the group unveiled a formal policy that, among other things, requires more detailed disclosure of board members’ industry ties.

“This is our business,” said Dr. Bruce Wilkoff, the incoming society president. “We either get out of the business or we manage these relationships. That’s what we’ve chosen to do.”

The society is one of a handful of groups that make public details about their finances. Most don’t. As non-profits, they must disclose their tax returns but not their specific sources of funding.

Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa,requested the information from the Heart Rhythm Society and 32 other professional associations and groups that promote disease awareness and research.

Their responses and reporting by ProPublica showed wide disparities in money the groups accept from medical companies, what they disclose and how they manage potential conflicts of interest.

With billions of dollars at stake, companies can court entire specialties by helping to bankroll doctors’ groups. The Heart Rhythm Society’s 5,100 members represent a particularly lucrative market.

One implantable cardioverter defibrillator — a device that jolts the heart back to a normal beat — can cost more than $30,000. A single electrophysiologist, a physician specializing in heart-rhythm disorders, can implant dozens a year. World sales of the devices totaled $6.7 billion last year, according to JPMorgan.

All the defibrillator manufacturers are at this week’s conference, including market leaders Medtronic, Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical, which together gave the society $4 million last year.

These companies and others not only provided financial support to Heart Rhythm but paid many of its board members: Twelve of 18 directors are paid speakers or consultants for the companies, one holds stock, and the outgoing president disclosed research ties, according to the society’s website, which does not specify how much they receive.

Board members at other medical societies have similar arrangements. The American Society of Hypertension does not post disclosures on its website, but records provided to Grassley show that 12 of its 14 board members had financial ties to medical companies.

Grassley, the top Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, said these groups commonly say the money doesn’t affect what they do, but he has doubts. “I don’t think it’s believable,” he said. “There are a lot of incestuous relationships that really bother me.”

Big Booths Boost Devices

As competition among cardiac-device makers has intensified, so have questions about whether their products are being used and marketed appropriately.

In January, a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that more than one in five patients who received cardiac defibrillators did not meet science-based criteria for getting them.

Weeks later, the Heart Rhythm Society disclosed it was assisting a U.S. Justice Department investigation of the issue.

Two of the society’s biggest funders — Boston Scientific and St. Jude Medical — have paid millions since 2009 to settle federal allegations that they improperly paid kickbacks to unidentified physicians to use their cardiac devices. Neither company admitted wrongdoing.

Top sponsor Medtronic also has disclosed to shareholders that the Department of Justice is investigating the advice it gave purchasers on how to bill Medicare for defibrillators and payments it made to buyers of the devices.

In a statement, Medtronic said societies play an important role in educating physicians about their devices. Boston Scientific declined to comment, and St. Jude did not respond to questions.

At this week’s conference, Medtronic is front and center with a 12,000-square-foot booth to demonstrate its products and allow physicians to examine them.

Medtronic spent $543,000 at last year’s meeting on a similar exhibit, part of $1.6 million it paid to prominently display its name around the conference and fund educational grants. The Minnesota device maker also paid unspecified speaking or consulting fees to eight of the society’s 18 board members.

Your (sponsor) Name Here

These slides show “promotional opportunities” – and their asking price – that the Heart Rhythm Society offered to medical industry sponsors at its 2011 conference. Not everything was sold.

Source: www.heartrhythmsupport.org/sponsorships.See our interactive graphic.

The spending befits the company’s dominance of the world market for implantable defibrillators. It sold more than $3 billion worth last year.

Next booth down is the 8,100-square-foot spread of rival Boston Scientific, with $1.6 billion in defibrillator sales last year. The company spent $1.5 million on the society in 2010 and paid speaking or consulting fees to seven board members.

Physicians must traverse these and other booths to reach “Poster Town,” where the latest research findings, a big draw of the gathering, are displayed. “It’s very hard to get through there without being accosted,” said Dr. Paul D. Varosy, director of cardiac electrophysiology at the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Eastern Colorado Health Care System.

‘Tag and Release’

Through the years, groups such as the Heart Rhythm Society have expanded the range of sponsorships they offer to drug and device makers. Companies can now fund Wii game rooms or put their names on conference massage stations and on the shirts of the masseuses.

Some deals give companies more than name exposure. Last month, the American College of Cardiology attached tracking devices to doctors’ conference ID badges. Many physicians were unaware that exhibitors had paid to receive real-time data about who visited their booths, including names, job titles and how much time they spent.

Dr. Westby Fisher, an Evanston, Ill., electrophysiologist, called the practice “Tag and release.” College officials say they’ll do a better job of notifying doctors next year.

Attendees at the Rhythm Society conference also have tracking badges. Society officials say exhibitors are not getting doctors’ personal information.

Two years ago, the American Society of Hypertension teamed with its biggest donor, Daiichi Sankyo, to create a training program for drug company sales reps. The society says about 1,200 Daiichi reps have graduated — at a cost of $1,990 each — allowing them to put the “ASH Accreditation symbol” on business cards.

In fiscal 2009, Daiichi gave the society more than $3.3 million — more than 70% of its total industry funding — according to financial records it provided Grassley. Daiichi makes four hypertension drugs.

“I think it’s an obscenity,” said former ASH president Michael Alderman, professor emeritus at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. “I can see how it would play out in the doctor’s office: ‘I’m a Daiichi sales rep. But let me tell you something: The American Society of Hypertension is backing me.’”

Alderman and some other prominent members of the group quit after a dispute in 2006 about industry influence.

Current ASH President George Bakris said the training program is science-based and doesn’t focus on specific drugs. The reps “ought to know what they are talking about,” he said.

The 1,900-member group has revised its policies since 2006, he said. Financial conflicts disclosed by board members, however, are available only to members, who must request them in writing and explain why they want them, according to the group’s conflict of interest policy.

A Question of Influence

Bakris and leaders of several other professional groups say industry funding is essential for much of what they do. It reduces conference registration fees, subsidizes the cost of continuing medical education courses and provides money for disease awareness.

Dr. Jack Lewin, chief executive of the American College of Cardiology, said the money is helping build registries of cardiac procedures that track side effects and flag whether physicians are using devices in the right patients.

The “circus element” of the exhibit booths doesn’t unduly influence attendees, Lewin said. “I don’t buy a soft drink just because of the advertising… I buy it because I like it.”

Researchers say companies are not spending millions solely for altruistic reasons. “If it weren’t influencing the doctors, they wouldn’t be doing it,” said Dr. Gordon Guyatt, a health policy expert at McMaster University in Ontario.

There are fledgling efforts to push medical societies toward stricter limits on industry funding: 34 groups have signed a voluntary code of conduct calling for public disclosure of funding and limits on how many people on guideline-writing panels have industry ties.

“The general feeling is that the societies need to be independent of the influence of companies,” said Dr. Norman B. Kahn Jr., chief executive of the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, which helped draft the code.

Grassley, too, is continuing his efforts to make the groups publicly accountable. In initial responses to his December 2009 request for information, some said they planned to post financial information on their websites. This week, the senator followed up with letters to some groups, asking why they hadn’t done so.

He hopes the political pressure succeeds: “You might conclude that maybe they don’t want to give the information out because it might be embarrassing.”