White attitudes at high altitudes: racism in early Rossland

With some recent content in the Telegraph regarding the rich cultural history of Rossland, it’s easy to see that we have a lot to celebrate in this town in terms of the different heritages that helped make this town what it is today. One can even say that Rossland is a microcosm of Canada’s multicultural mosaic. However, there is a darker side to this as well, which is also microcosmic of race relations not only in Canada but worldwide as well: this town that so many from so far away called home also had its share of prejudice and bigotry.

This can be attributed to the Victorian attitudes prevalent at the time of Rossland’s founding: it was as rich white man’s world in the 1890s. But as the saying goes, ‘you don’t know where you’re going till you know where you’ve been’, and I think it’s worth exploring some of the racial issues that existed in our town’s past.

The Chinese who came here are the obvious place to start, but I was surprised to learn through some of my research that in early Rossland there was a significant Italian population, and they were treated with much mistrust when they arrived. However, the marginalization they ran into was less racially and more politically motivated.

The Italian community in Rossland in the 1890s was comprised of about 156 people and included some women. Two thirds of the men worked the mines and were between 20 and 35 years of age. The problem was that many residents of the town believed that mine managers were deliberately recruiting Italians in order to weaken the labour unions. Management saw it as a plus to have a mix of races working the mines because it undermined the labour movement. One mine manager quoted as saying, “How to head off a strike of muckers and laborers for higher wages without the aid of Italian labor, which is offered so plentifully, I do not know.”

Rossland was a two-newspaper town back then, and the attitudes towards the immigrants were apparently quite sneering. However, the labour unions themselves seemed to believe that the management’s strategy was backfiring, pronouncing the influx of Europeans to Rossland “a failure” on the part of management. In fact, the union seemed to be loving the Italians! One executive said publicly, and quite patronizingly, “an Italian takes to unionism when he has an opportunity like a newly hatched duck to a pond of water.”

It seems apparent that the Italians were seen as pawns, stuck between the agenda mine management and labour unions, and with all the political side taking and potential tensions that would naturally come with the territory.

But by far it was the Chinese in Rossland who had the toughest time. Legally, they were prohibited from working in the mines because of their race, and therefore, in most cases, they were relegated to eking out a living with low paying service industry jobs. In the 1901 census, the number of Chinese men in Rossland broke down like this: 231 total Chinese men (there was at one time one woman, back in the 1890s, but from what I read, her own countrymen didn’t even want her there and I’m not sure what came of her; by census time she was gone) who comprised 4% of the total population, and about 75% of those were lodgers. From this 231 men, 97 were launderers, 53 were cooks, 32 were gardeners, 20 were general labourers. Additionally, there were eight merchants and three restauranteurs.

The Chinese here were subjected to physical violence and intense scrutiny from the law because some of them were known gamblers and keepers of opium dens. After a prostitute named Josie died of an opium overdose in a Chinese-owned den, there was a series of raids on these opium dens; the police chief explained that this was because too many white people were becoming corrupted by frequenting them.

But the pervasive attitude of the time towards the Chinese, not only in Rossland, but in BC at large, was that they were a filthy lot who carried diseases. The following is an excerpt from an editorial that was printed in one of the local papers, and it illustrates very strongly the thinking of the time:

From personal observation the mayor was able to say to the members of the city council that [the Chinese] quarter is in the filthiest possible condition, and that it is the worst kind of menace to the health of the community…It is utterly impossible that with such environment these people can be mentally or morally healthy any more than they can be physically so. The taint which their bodies must receive from their surroundings cannot fail to communicate itself to their moral natures….Wherever they go, they will threaten the white community in whose midst they exist, with all the dangers of outbreaks of loathsome diseases.

In 1901, a Royal Commission studying Chinese and Japanese immigration to British Columbia visited Rossland and found that almost unanimously most mine managers, business people, and union leaders wanted Chinese immigration to the area stopped completely. They apparently didn’t see any value in the jobs the Chinese took on, even though they were vital to keeping a mining town running. Perhaps they hadn’t found their shirts were coming back white enough from their local Chinese laundry.

Locals also resented their Chinese neighbours for importing their own liquor, sending spare money back home, and not assimilating to the white culture around them. When one of the Chinese community died, his body would be interred in a special corner of the Columbia Cemetery (the one in Happy Valley), but could only remain for three years. After that, it was the responsibility of the Chinese to exhume the bones and send them back to China to be buried in their homeland.

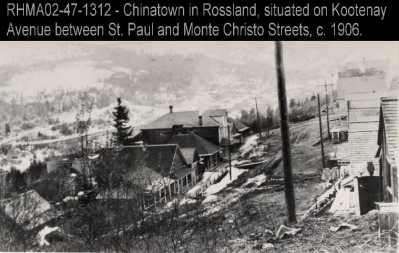

While attitudes changed somewhat over the decades, there is a very revealing set of oral interviews posted on the Rossland Museum web site where some old timers offered up their experiences and memories of the Chinese for posterity’s sake. There is almost a fondness expressed by the three interviewees, Ike Glover, Warren Crown, and Harry Lefevre. One said, “The Chinamen were good citizens and they never bothered anyone. The Chinese were a good race of Chinese in Rossland and they were never any trouble. They were very beneficial to the people of Rossland.” Another said, “The women used to say that no one could wash a white shirt and iron it like a Chinaman.” Yet another quote says, “There were about ten to fifteen stores where the first railway depot was located on LeRoi Avenue between St. Paul and Monte Christo Streets. There was also a Josh house and one store that sold nothing but herbs and Chinese medicine. Their stores were very drab.” One account reports that the Chinese imported large turtles – as in turtles large enough for kids to ride – for medicinal purposes, and also bought bear gall bladders and paws for medicine, too.

So while there is a patronizing tone to these reminiscences, it’s evident that at least someone eventually appreciated them, even if it was in an ‘oh, I guess those guys weren’t so bad after all’ kind of way.

Back when I was growing up, Rossland was a largely white town. I remember when I was in elementary school a family that might have been East Indian moved in at the top of Thompson Avenue. I remember that they kept very closely to themselves. I only remember seeing them in their own yard, not around the community. They always struck me as lonely. Today Rossland boasts a very international population; however, with a few exceptions, it’s still a mainly white town. Why is this? Even Inuvik up in the Arctic has more visible minorities there than we do! They just got a little mosque because, with a population of 100 to begin with, there are enough Muslim families up there to warrant one.

If we are who we say we are – friendly, community-minded, forward-thinking, progressive, etc. – why are there not more visible minorities here? Is it karma?

It’s a question worth contemplating, I think.

Sources: