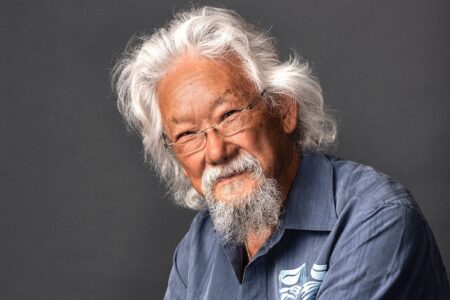

INTERVIEW: Joanne Schroeder – Deputy Director of the Human Early learning Partnership at UBC

According to a recently-released study by UBC’s Early Learning Partnership BC, as a whole, has an issue with underdeveloped kindergarten-age children. According to the study, approximately one third of BC’s five-year-olds are vulnerable. Rossland, however, seems to be bucking the trend and came out as the top-ranked community in BC with 0% of our youngsters categorized as vulnerable.

This week, the Telegraph caught up with Joanne Schroeder, the deputy director of the Human Early Learning Partnership to learn just what ‘vulnerable’ is, how BC is doing, why Rossland is bucking the trend, and what it all means going forward.

We’ve read in the report that Rossland came out ranked number one in terms of the least number of vulnerable children in the province. Tell us a little more about the study itself.

It’s a study that basically provides a snapshot or a census, really, on how developmentally-ready our children are as they enter kindergarten. It provides a look back at the qualities of experience they’ve had prior to entering school. The information is collected through kindergarten teachers. They fill out a 100 question survey for each child in their class. Those surveys, which are anonymous, come back to UBC and we do the analysis and then we are able to see how kids are doing across BC.

What types of questions are kindergarten teachers being asked to evaluate their children on? Can you give us a few examples?

It would ask things like if they are able to climb stairs, if they are able to properly hold a pencil, if they are able to recognize letters and numbers, if they cry when their parents leave them, if they fight with other kids or are shy and those kinds of things. There are questions about physical development, language and cognitive development as well as social development.

So when we read that Rossland has 0% of our kindergarten children labeled as vulnerable what exactly does that mean?

It means for this particular group of Kids in Rossland–the kindergarten population in 2010–none of them fell below what we call our vulnerability cut off. It’s relatively complicated statistical system but after we had been across the province the first time with about 45,000 children’s data we set a mark at the bottom 10% of the scores and then from there on in subsequent studies any child who scored below that mark was considered vulnerable.

These kids that are vulnerable are going to continually struggle throughout their school years.

How does this year’s 0% vulnerability score (the best in the province) compare with Rossland’s previous scores in over the last ten years?

The first couple of years that we did the study, about 25% of Rossland kids scored as vulnerable and last year it was about 8 %. One thing to note in a place like Rossland though–and I don’t want to minimize that having no children vulnerable is an interesting result–is that in small places the numbers tend to fluctuate more because we report in percentages. Three or four kids changing in a small area will alter the percentage much more than a few kids changing in a larger population area so these numbers, although good, will fluctuate.

We’ve never had a result of 0% vulnerability before either, so that’s something to take note of even in a small community.

The take-home message for the study overall, however, is that across the board for the most part in BC there are too many kids–over third–that are behind developmentally when they are starting their school career.

We’ve been doing the study in BC for the last ten years now and we do different sections of the province each time so this would be the fourth time we’ve done it in Rossland. Each times the results would be a little different but they do appear to be trending in the right direction.

We know Rossland came in on the top of the scale. What are some of the places that score the lowest?

There are lots of places that are higher than 50 and 60 percent vulnerability. We find those in the downtown Vancouver neighbourhoods, in Prince George, the Comox Valley and all over BC.

The important thing from our point of view is to look at the data over time. In most places we will find that over 25% of kids in BC are vulnerable over the past ten year period.

Now that you’ve got ten years worth of data, what is the next step? What gets done with the data you’ve collected?

The research is intended to inform policy makers so we work closely with governments and people in the early childhood education world to help change policy and boost programs that ultimately help our kids get to where they need to be developmentally before they begin school.

The thing that is of most importance to us is that we reduce the vulnerability with children entering kindergarten. Although with the kids in Rossland this year it was a good story, across the province of BC about one third of kids are vulnerable when they enter kindergarten and one third of our kids are already behind when they start their educational journey. It’s important to us to help reduce that number everywhere and we can only do that through providing public investment into healthy families and children. Children can only do well if families are doing well. We’d hope this report spurs on programs that allow families achieve balance while caring for their children to have enough time and resources to raise their children.

This data seems to clearly show a pan-BC need to do something to improve the development of our children. Now that we know there is a need, what can be done about it to improve the situation?

What families need to care for their children is time and supportive services so it would be of tremendous value to have things like extended parental leave policies to have both mothers and father stay home with children in the first year. We know that people are working longer and longer hours so there could be things to improve employment policies to allow people to work shorter times and still have active benefits. The big thing we need to have after children are 18 months old is quality early childhood learning programs. Access to childcare programs in BC is very limited. Lots of kids are in programs that may not be meeting their needs. Those are the biggies.

The other thing is to engage the whole community. The old adage that it takes a village to raise a child is so true. If local businesses can do things like making their businesses child friendly with family friendly policies that allow their employee the opportunity to care for sick children and those types of things.

In analyzing the data have you been able to pick out some commonalities between towns that score similarly? Can you identify some things that certain cities have going for or against them?

For sure we know that in places where children are doing better you’ll typically see collaboration between service providers and people interested in children like the school district and early childhood community. You would most often see strong relationships in the community where people are working together towards creating more quality services for children.

On the other side, we know that things like poverty obviously are not good for children. In communities of high economic social advantage children do better. Most of the vulnerable children in BC, however, are living in middle class families and that’s mostly because that’s the situation most of our children are in.

Moving forward, how will your group build on this study and take it further?

The important work we’re doing here now is linking our kindergarten entry results forward in time to see how those kids are doing as they proceed through the school system and to understand more about trajectories in development. We’re working towards being able to understand some of the characteristics of those vulnerable kids from birth onward. Really we’re working on having solid date to create a cradle to career trajectory to understand children’s development and to understand the long term impacts on our kids if we don’t do things for them in their very early years to make sure they are not vulnerable.

For more background on this study see Janet Steffenhagen’s story on the UBC study