Editorial: Our Choice of Voting Systems -- Part Five

Last week, I promised to summarize in this part the differences between our current voting system, called First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation systems.

Most people understand how we vote now, with FPTP:

We put a check or an X on the ballot beside the name of the person we’d most like to see representing us in the Legislature. We may vote for a candidate because we know her or him, or we may vote for them because they belong to the party we like best. Or we may vote for them because we think voting for them is most likely to help us avoid being represented by someone else whose party we don’t want to get into power; that’s what we call “strategic voting.”

The candidate who has the most votes in a particular riding is elected. This victory is only rarely achieved by a majority of the votes, because we have more than two political parties. So, we are often represented by a candidate who is not supported by the majority of the voters in our district.

And under FPTP, the party who ends up having total power in the Legislature is often a party who gained all that power with a minority of the votes; so, again, the province ends up being completely controlled by a party chosen by a minority of the voters, instead of a majority.

That’s the system we have now. Let’s be clear: it’s a great system to use if there are only two political parties, and if gerrymandering is eliminated.

Fans of FPTP should also note that FPTP would play a large part in all of the ProRep systems being considered, to elect local MLAs directly. (In the Rural-Urban PR system, FPTP would apply only to the rural districts.)

Proportional Representation:

Any of the three systems being proposed on the ballot this fall would ensure that representation of parties in the Legislature more closely matches their level of support by voters. If a given party gets 40% of the votes, it would have about 40% of the Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs); and so on. It will probably be rare for any party to achieve a majority of the votes; under ProRep, parties would have to work together to achieve change. That means that legislative change would have to be supported by parties representing a majority of voters, instead of a minority of voters. To me, that seems like a more transparent, fair, and accountable way to govern.

Let’s review, first, what criteria were imposed for a system of Proportional Representation (ProRep) to be included in the referendum this fall. All ProRep systems on the ballot had to:

· Provide a reasonable degree of proportionality;

· Retain local representation;

· Be simple enough for voters to understand and use;

· Keep the number of MLAs from increasing by more than eight — if at all.

All three systems offered on the ballot meet those basic requirements. For many voters, that knowledge will be enough, and they may decide to answer only the first question on the referendum ballot: the one that asks whether they want to continue to vote by FPTP, or change to a ProRep system.

For those who wish to answer the second question – which system of ProRep they’d rather use – read on. Bear in mind the similarities that all three systems share, as listed above.

Differences among the three ProRep systems:

Under Dual-Member Proportional, most of the Electoral Districts in the province would become twice as large – because most would be amalgamated with an adjoining district, except for the largest rural districts. But each of the new, larger districts would have two MLAs, so there would still be the same number of MLAs per unit of area. The first one would be chosen by FPTP; the second would be chosen based on votes and the need to achieve proportionality province-wide. Constituents who wanted to talk with their MLA would have a choice of which MLA they felt more comfortable approaching. This system would have a very simple ballot – just as simple as the current FPTP ballot, in my opinion.

Under Mixed-Member Proportional, MLAs would be elected by FPTP in each electoral district, and then “list” seats would be added to achieve proportionality. They would be allocated on a regional basis, to increase the local nature of representation by those MLAs. Electoral districts would be somewhat larger than they are at present, to avoid having to increase the total number of MLAs by very many. The ballot could be very simple, if “closed” lists are used, or a little less simple if voters are enabled to vote directly for “open” list candidates.

Under Rural-Urban PR, voters in densely-populated urban or semi-urban districts would vote using the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system, and voters in rural districts would use the Mixed-Member Proportional system: electing MLAs directly by FPTP, with a few “list” seats to achieve proportionality. The ballots for both systems are relatively simple.

Decisions to follow the referendum:

If the majority of voters choose to continue on with our current voting system, then there will be no decisions to make about how to implement ProRep. But if the majority of voters vote for a ProRep system, there will be a number of decisions to make – about the exact form of ballots, open lists vs closed lists, electoral district sizes and where boundaries will be, and so on.

Part Six of this series will discuss the most important of those decisions, how they will be made and by whom, if voters choose ProRep for BC.

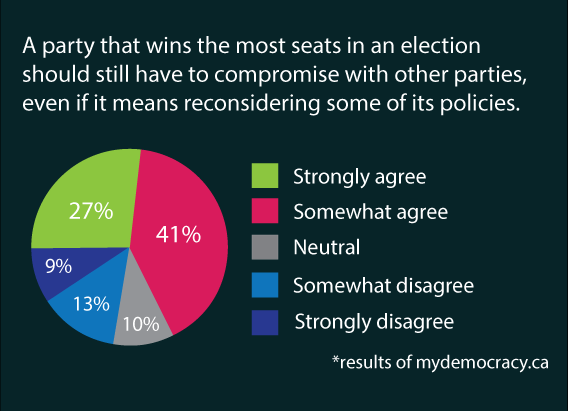

Below: a graphic from FairVote BC: