The Hunger Games...and other dystopias

The Hunger Games have arrived, a storm of popularity that is selling millions of books and filling movie theatres. Suzanne Collins’ dystopian story is about North America in ruin after an unspecified cataclysm leaves the rich in absolute power and the poor as their slaves. The story has a credibility because it extrapolates from the present, with the roots of its chaos, poverty, injustice, savagery and heroism firmly anchored in today’s economic, political, social and environmental conditions.

Granted, The Hunger Games is a story written for young adults by an adult. Literary critics correctly note that it ingeniously possesses all the formulaic attributes that appeal to youthful minds in the turmoil of full adolescence rebellion against the wisdom of adults. But its success is something more than marketing cleverness. Adults have also taken an interest in the story because it fits the multigenerational cynicism of our times and is wholly compatible with the deep uncertainty that haunts the promise of a safe, secure and prosperous future.

If The Hunger Games were an anomaly, if it stood alone as a one-of-a-kind dystopia, it could possibly be dismissed as a culturally meaningless entertainment. But it is part of a trend that has obsessively occupied 20th century literature and thought. Therefore, it is significant.

The 20th century did not begin well. The dysfunctional values of the 19th century stumbled into the disaster of World War I. Then came the financial recklessness that caused the Great Depression of 1929. World War II followed, then the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the protracted Cold War with its tense threat of global nuclear annihilation. While hundreds of loaded intercontinental ballistic missiles still sit poised for firing, we are welcomed into the 21st century with enough serious environmental stresses — population, pollution and pillaging — to shake the confidence of any civilization.

The psychological and philosophical impact of all these stresses can be tracked by culture. War poets, playwrights, writers, painters and musicians have tried to understand the wholesale inhumanity unleashed by the mass tribalism of war. The Dada movement of 1916 simply abandoned understanding altogether and resigned existence to meaninglessness. The Existentialists abandoned society for the sanctity and burden of the lonely individual. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) castigated a society numbing itself with drugs and escapism. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) warned about the machinery of state victimizing societies by centralized control. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) also cautioned about totalitarian rule. William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954) captured the dark and destructive instincts lurking in the heart of humanity. Neville Shute’s On the Beach (1957) dramatized the devastating consequences of a global nuclear war. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) was one of a flood of more current dystopian novels.

Now environmental fear has been added to the list — terrorism is tragic to individuals but it doesn’t threaten the structural foundations of society like the looming and troubling ecological upheavals that scientists predict. So bookstores, television channels, movie theatres and media commentary propagate warnings of climate change, ocean acidification, species loss, excessive population, food shortages, societal havoc — choose your preferred worry. No wonder that The Hunger Games has appeared as a prevalent theme in the literature of young adults.

Phyllis Simon, co-owner of Vancouver’s Kidsbooks, notes that “the top five or six [bestsellers] are dystopias,” all linked to climate catastrophe (Maclean’s, Apr. 16/12). The theme of Exodus is a world drowning in rising sea levels because of melting ice. The Way We Fall explores society on the verge of collapse because of an escaped killer virus — the same threat, incidentally, that Stephen Hawking identifies as his choice of immediate dangers facing our civilization. The theme of The Hunger Games is just one expression of a fear that is infecting all levels of society, from children and young adults to senior citizens.

Such worrisome cultural markers are supported by empirical evidence that our affluence may not be as satisfying as we are induced to believe. Mental health issues cost Canada $50 billion per year in lost production and efficiency. Psychiatric illness in Europe, the New Scientist reports (Sept. 10/11), is the continent’s largest health problem. “Almost 40 percent of the region’s population — around 165 million people — experience a mental disorder each year, such as depression or anxiety…”. Anxiety is the most prevalent at 14 percent, followed by insomnia at 7.0 percent and depression at 6.9 percent. About 10 percent of other psychiatric conditions complete the spectrum of disorders linked to the stress of our lifestyles — not exactly ringing endorsements for a materialistic, consumer society that is busily wrecking the many of the planet’s crucial ecologies.

When our recent and present behaviour is considered in its totality, it reveals an undercurrent of apprehension about the strategies that are guiding our collective lives. The material wealth we have used as the dominant measure of our success hasn’t dispelled a growing doubt about the wisdom, prudence or sustainability of continuing on our current course. The economic, social, political and environmental conditions in which we presently find ourselves are disquieting and stressful, not a source of happy contentment but of worry and tension. The Hunger Games is just the latest expression of this mood.

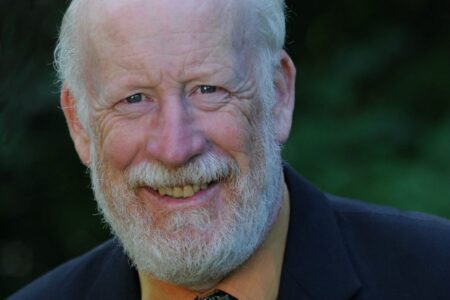

Ray Grigg is a weekly environmental columnist for the Campbell River Courier-Islander. He is the author of seven internationally published books on Oriental philosophy, specifically Zen and Taoism. This piece originally appeared in the Common Sense Canadian.