Lui Joe: Uncovering Rossland's Chinese history

My little series of historic pieces about Rossland’s past has been quite the adventure to say the least because the research has been very revealing. Having done my share of essay writing and research projects while studying Classics in university (one of the quirks of a creative writing major was that it involved almost no research projects or essays at all, so I had to get my fill by signing up for a more academic minor just so that I felt I’d paid my dues. Well, that’s not exactly the reason; I got A’s in Latin so I decided to delve more into the history I was discovering while translating Cicero), I find that there is something comforting and nostalgic about this kind of information gathering. I feel student-like again – only without the loans.

Interestingly, a creative writing professor of mine once told me, when I mentioned where I came from, that in the future I’d no doubt be mining Rossland for all it’s wealth of quirky characters and unique experiences. He might not have known Rossland was a mining town, so he probably wasn’t aware of the irony of using the verb “mining.” Turns out it was prophetic in a way; though I’m writing and researching (mining) Rossland history for a more formal, journalistic purpose and not the Great Canadian Novel I was all keen on during my uni days, it’s still been an interesting development in my life.

Inspired by the new, as yet, unnamed trail that was recently constructed in lower Rossland, I spent the weekend researching Lui Joe and Rossland’s Chinese gardens. Talk about mining! Sources are limited, some are conflicting, and in some cases, they are downright annoying.

For instance: I came across a great document online called “First History of Rossland” that was published around 1897 or so and written by some character called Harold Kingsmill. It’s an incredibly detailed ight-page account of the early settlement of the town, it’s early buildings, how the downtown developed, who owned and built what buildings, and how Rossland, in a very short period of time, went from a mucky mining camp to thriving town of thousands. It was so detailed, someone with way more artistic talent than I have could easily create an excellent map or rendering of downtown Rossland pre-1895 and it would be pretty wicked. However, no matter how much the author enthuses about how hardy and enterprising the fathers – and mothers – of this town were, it’s a very white-centric take on Rossland history: there is not one single mention of any of the over 200 Chinese people inhabiting Rossland at the time or any mention at all of the supporting roles they had in the evolution of Rossland from nowhere to somewhere.

I shouldn’t be surprised; this was the Victorian era, of course. Racism and bigotry were pervasive, and the fact that the Chinese are totally absent from this publication is indicative of the extreme marginalization the Chinese community endured at that time in Rossland. Victorian values and perspectives were vastly different from ours, and that is reflected in the biases of not only Kingsmill’s writing, but of much historical documentation of the time. On the one hand, I should be grateful that times and attitudes have changed, but on the other, I’m a tad bit resentful as a researcher that the exclusion of the Chinese from the early documented histories of this town has left little information behind about these people.

The Chinese have a long history in BC, harkening back to 1788 when 50 artisans settled in Nootka Sound, where they helped a guy named Captain John Meares create a trading post. The purpose of this was to encourage the trade of sea otter pelts between the Natives and the folks in Guangzhou, China. Meares was a British fur trader and sea captain, but eventually his small empire fell apart when the Spanish took control of his trading routes and stranded many of his Chinese crew in the area. Some of these men settled down there and married Native women.

But of course the most significant migration of Chinese people to BC took place during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Between 1880 and 1885, approximately 15,000 Chinese men came to Canada, mainly from the Pearl River delta of Guangdong province between Guangzhou and Hong Kong. During our provinces various gold rushes, many Chinese migrated to Canada from San Fransisco to either make money from gold panning or in ancilliary roles necessary to the running of a mining camp of town. No doubt this is how many of the 200 Chinese men and one Chinese woman came to Rossland in the mid-1890s, though it is also notable that Edgar Dewdney, builder of the Dewdney Trail, employed about 100 Chinese workers for the stretch of the trail between Rock Creek and a place called Wild Horse, and many of these Chinese labourers were stationed for work on the trail around Fort Shepherd. According to one source, some of these men stayed around the fort after that part of the trail was complete in order to pan for gold in the tributaries of the Columbia in the area.

Due to white superstition and white bigotry, Chinese men were not allowed to work underground in the mines in Rossland. Instead, they worked as cooks, servants, shopkeepers, launderers, and gardeners. Some also kept opium dens and one was even a fantan (a gambling game) expert.

But it was the Chinese Gardens, located in the southeastern section of town below Thompson Avenue, opposite the Catholic cemetery and stretching down to Trail Creek, that was the most significant contribution this immigrant community made to Rossland. On May 13, 1903, one of Rossland’s daily papers The Rossland Miner reported that “the Chinamen have cleared and cultivated an area of 50 or 75 acres” and goes on to say “these lands are clear of brush of every description, and innumerable cairns indicate the patience with which the cultivators have gone over every inch of the soil and removed the impediments to vegetation. The fields are comparatively tiny plots, but the richness of the soil makes large holdings unnecessary.” These gardens provided the rapidly expanding community of Rossland with fresh produce for 50 years.

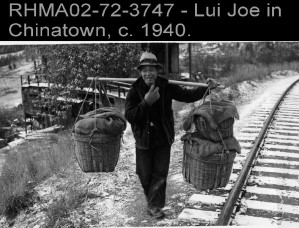

This means that for decades vegetable peddlers walked from way down in lower Rossland up to the town proper carrying huge baskets slung across the backs of their shoulders with a yoke in order to sell their goods. In the winter, they stored their produce in root cellars and made the trip less often.

Lui Joe was Rossland’s last peddler. He lived in the Thompson Avenue area, and according to local historian Jackie Drysdale, there are a few old timers in town who still remember Lui Joe. Over the phone, she quoted one long time Rossland resident, Mickey Irwin, who, with her husband Jock, went to visit Lui at his home, as saying “you couldn’t even call it a shack. It had a dirt floor.” Drysdale recalls another old-timer telling her about the grooves in Lui’s hands and shoulders from years of carrying that yoke up and down the mountain.

Before green grocers and grocery stores monopolized the sale of produce in town, Lui could be seen with a couple of his fellow Chinese gardeners hanging out at the corner of St. Paul and Columbia avenue, having a smoke and a chat before going their separate ways to sell their wares around town. They each had their own routes, and they never trod on anyone else’s territory.

On January 6, 1946, The Rossland Miner featured the headline “Old Timers Among Chinese Residents.” The story was about the 10th annual Christmas dinner at the Chinese Masonic Hall, which had been a long-time club and hang-out spot for the local Chinese community. When it opened October 12, 1903, there were 100 members. By the Christmas feast of 1946, there were 16, and Lui Joe was on the list of attendees. The eldest was a man named, according the the Miner, Mow Fong, and he was over 80 years old.

Just four years later, in 1950, the Chinese Masonic Temple, the last remnant of a once-bustling Chinatown located in the LeRoi Avenue-St. Paul St. area, was torn down. And apart from part of a wall and a large rock that might have been used as a knife sharpener, nothing physical remains of the Chinese gardens today.

It is fitting, therefore, that residents have suggested the new trail that goes through the former Chinese gardens be named after Lui Joe. As Chair of the Heritage Commission, Drysdale says, “The [Heritage] Commission endorses the idea of naming the trail the Lui Joe Trail” and notes that the commission has put their endorsement in the form of a motion, which will eventually come before council. Drysdale continues: “there is very little concrete connection with the Chinese in the early days of Rossland’s history.”

Tell me about it! In a town that exists due to mining, it certainly takes a miner of a different kind to find some of the more obscure stories out there that are just as important as the well-documented ones. I am reminded of the adage, “history is written by the winners.” Well, Harold Kingsmill’s publication certainly proves that one right, but I do hope that Lui Joe and the Chinese gardens will eventually have their say, too.

Sources:

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

Roaring Days: Rossland’s Mines and the History of BC, by Jeremy Mouat

The First History of Rossland, by Harold Kingsmill

Jackie Drysdale, Chair, Rossland’s Heritage Commission