Op/Ed: How much do we care?

Few people here can recall war efforts in Britain during the Second World War, but more of us have read about them. Most everyone pitched in; they sacrificed personal comfort and convenience for the common good, obeyed blackout rules, saved even gum wrappers for the aluminum content, contributed pots and pans, rationed food, spent time volunteering to make bandages … it was an all-out effort. People cared.

But then, the threat was obvious. Bombs were falling, killing people and blowing up their homes and workplaces.

Some think the threats we face today are obvious too: flooding has recently disrupted many communities locally and globally. Now, wildfires are raging over hundreds of hectares around BC and across Canada’s prairies, and weather forecasters are predicting a hot dry summer – prime wildfire conditions. We stand to lose just as much as in any war, but who’s the enemy here? And do we really care what happens ten or twenty years from now?

Sandbags and water bombers aren’t a long-term solution for these bigger floods and fires. Human-caused climate change is intensifying the conditions that make both floods and fire seasons more destructive.

Recent work by a research group, led by Professor Petra Döll of Goethe University Frankfurt, has examined the likely hydrological differences between a future world in which average global temperatures have risen by two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial norms, and a future world in which average global temperatures have been kept to an increase of one and a half degrees Celsius. Just half a degree . . . but the research showed significant differences in the likely results.

An increase of two degrees will, according to the researchers, increase flood risks over an average of 21% of the world’s land area. But if the increase in global average temperature is kept to one and a half degrees, they say that only about 11% of the land area is likely to be affected. Not only for floods but also for drying trends – at one and a half degrees of increased temperature, the changes in hydrological effects will be significantly smaller than at two degrees. For scientists who can appreciate the full report on the study, click this link. In short: the higher the average global temperature rises, the worse off we’ll all be.

Two degrees of warming has long been touted as an “acceptable” limit, but please note: there is no evidence whatsoever that two degrees of warming will preserve life and society as we know it. Rather, there is mounting evidence that two degrees of warming will result in widespread damage and economic catastrophe for many, and could result in run-away climate change. Exponential changes make for startlingly abrupt endings.

For a much more comprehensive article on the impacts of climate change, read this long but absorbing 2017 article by David Wallace-Wells from New York Magazine.

Meanwhile, for a dollop of hope, an optimistic group of international scientists at the International Institute for Applied systems Analysis has created a scenario which they claim could limit global warming to one and a half degrees Celsius: “Our scenario meets the 1.5° C climate target as well as many sustainable development goals, without relying on negative emission technologies,” claims the abstract.

Arnulf Grubler, lead author of the study and IIASA acting program director, is quoted in Science Daily: "Our analysis shows how a range of new social, behavioral and technological innovations, combined with strong policy support for energy efficiency and low-carbon development can help reverse the historical trajectory of ever-rising energy demand."

Their suggested fixes include transitioning away from fossil fuels and using renewable energy, reducing the energy used to move people and goods and to produce those goods , to keep homes and offices comfortable; the use of shared an “on-demand” electric vehicles; stringent standards for energy-efficiency in buildings; and more accessing services instead of owning things; and eating a diet richer in nutritious plants and lower in red meat, while increasing forest cover globally.

It's good to have some hope. The trouble is, achieving the hoped-for state demands dramatic changes, and an unpredented degree of dedication, political will, and co-operation. Do we have it in us, globally, to do all those things? Do enough of our decison-makers care?

Dr. Mayer Hillman is an 86-year old architect, town planner, social scientist and a senior Fellow Emeritus at the Policy Studies Institute, University of Westminster. He has devoted a great deal of thought, observation, research and analysis to the issue of climate change, and on his website he states:

“I have concluded that, as a matter of great urgency, governments across the world must set mandatory targets based on a global agreement on per capita rations, delivered in the form of personal carbon allowances. Critically, having set these targets, those governments must then ensure that they are met.”

In other words, he thinks the only solution to curbing climate change is to limit – to ration – the amount of carbon anyone is permitted to release into the world, without trading entitlements. Cap, but no trade. Only that measure would inspire people to find ways of reducing their carbon footprints to the necessary level. His idea is compatible with the work of Arnulf Grubler and associates. Is Dr. Hillman holding out hope for the future of the biosphere?

Not really. He points out that governments are more interested in keeping people happy than in acting effectively to preserve the life-supporting capacity of the planet; “ . . . for electoral reasons, governments are strongly motivated to pursue strategies which appeal to people’s short-term self-interest, with little or no regard to the social and environmental consequences.” In other words, politicians care more about being re-elected than about saving life on earth. So they work to appeal to voters' short-term self-interest instead.

In an article in The Guardian, he is quoted as stating, with a brilliant smile, “We’re doomed.” In the most recent climate-change article on his website, published in April of this year, he concludes, “In all conscience, we are currently locked into a process whose inevitable result will be a planet with little life left on it. The issue is the most important one facing the world. As such, it must top the international political agenda.”

Readers, examine the actions of world leaders, including our own Prime Minister and his cabinet, and answer for yourselves the question of whether addressing climate change tops the international, or even the national, political agenda. Or not.

And ask yourself: does humanity need to make changes, to keep civilization from degenerating into widespread war, and a series of “natural” disasters – storms, floods, fires, droughts and famines — that could knock us back into something like the stone age, if not extinction? So that life on earth can continue without losing too much more of its health and diversity? Or do you think everything is fine, no problem?

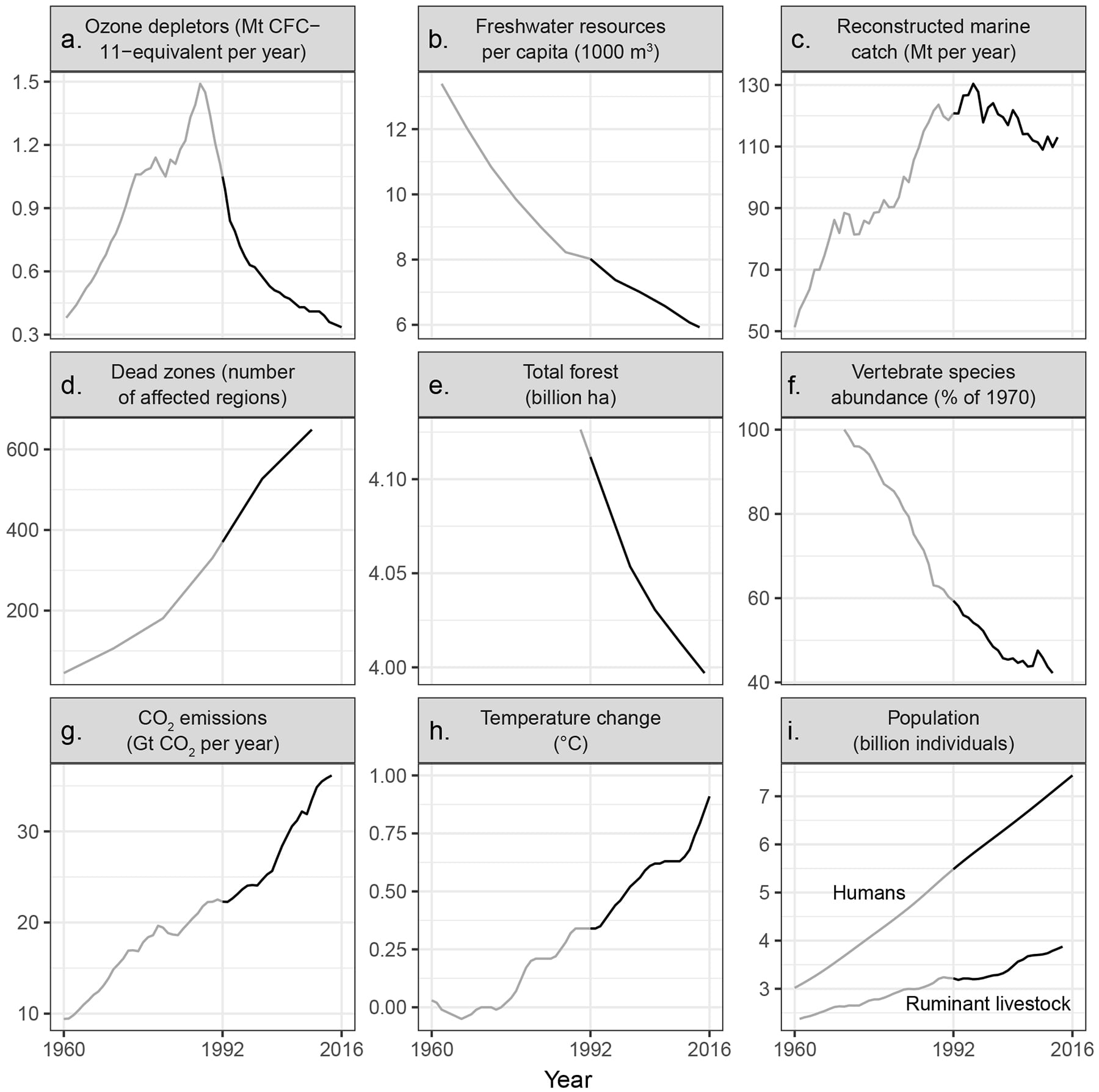

If you think it’s all fine, no problem, and that you understand the state of life on earth better than the over 20,000 scientists who have now signed on to the “Scientists’ Warning to Humanity” first issued in 1992, and the “Second Notice” published in 2017, try reading the “Second Notice.” It’s not that long, it’s packed with information, and it makes very sensible concrete recommendations about the changes needed to ameliorate our planetary crisis, but also notes that time is running out to take effective measures. If you can't take time to read the full article, here are a few relevant graphs from the Second Notice showing changes from 1960 to 2016 (only the first graph contains good news):

That break in the graphs at 1992 shows the date when the initial Scientists' Warning to Humanity was issued. The darker lines on the graphs show how the indicators have changed since they issued their first warning and their recommendations.

The final question for today is, how do we get politicians to care enlough to act on those sensible recommendations?