Canada has some of the world's last wild places. Are we keeping our promise to protect them?

To meet one of its most critical conservation targets by 2020, Canada must protect a massive amount of land — roughly the size of Alberta — over the next year and a half. So where will this protection occur and can it be done in a way that actually benefits biodiversity?

By Gloria Dickie, from The Narwhal

The world is currently facing down what scientists are calling the Sixth Extinction Event — a dramatic decline of the world’s living species, driven in part by habitat loss.

To help combat this, in 2010, 195 countries (including Canada) signed on to an international conservation treaty designed to slow the pace of biodiversity loss by protecting more of the world’s ecosystems.

Last week’s announcement of a new 14,000 square-kilometre Indigenous Protected Area in the Northwest Territories is just the beginning of Canada’s efforts to meet the Convention of Biological Diversity’s 20 Aichi Biodiversity targets.

As a signatory of the Aichi Biodiversity targets, Canada has developed its own in-house conservation plan that folds Aichi’s targets into 19 specific goals.

One of Canada’s goals — called Target 1 — calls for 17 per cent of terrestrial areas and inland water and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas to be conserved by 2020.

So, with the latest announcement in mind, how is Canada’s progress coming along?

All eyes on Target 1

Canada contains more than 9.9 million square kilometres. Seventeen per cent of that amounts to roughly 1.7 million square kilometres.

At this point, Canada has protected around 10.5 per cent of terrestrial areas, and 7.75 per cent of marine areas, making it one of the targets with the most progress — but Canada still lags behind other nations.

Tanzania, for example, has set aside more than 33 per cent of land for protected areas.

Canada needs to make a big push — roughly the size of Alberta by land area, over 650,000 square kilometres — in the next year and a half to make it to the finish line.

Canada’s next update on the progress of meeting these biodiversity conservation targets is due in December, but meaningfully and systematically protecting land is harder to do than one might think.

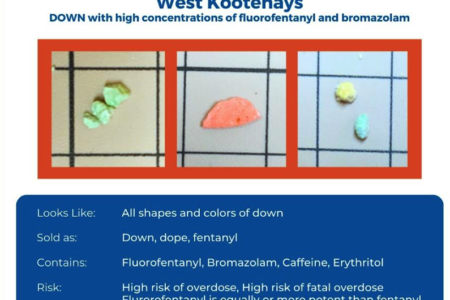

“Most of our population is along the southern border, and that’s also where we have the highest density of species-at-risk,” Laura Coristine, a researcher at the University of British Columbia-Okanagan Biodiversity Research Centre who has studied Canada’s progress on Target 1, told The Narwhal.

“The biggest challenges relate to where people are on the land versus where biodiversity needs protection.”

The collision of population density with biodiversity needs makes conservation efforts that set aside land as “off-limits” more difficult to implement.

Overlapping ranges of Canada’s species at risk. The red area, showing high numbers of species at risk, also overlaps with Canada’s most densely populated areas. Map: Coristine et al.

Researchers also recognize that protecting species-at-risk is just one facet of what federal, provincial and Indigenous governments should be aiming to achieve with setting land aside.

Beyond the needs of at-risk wildlife, key conservation areas can also help beef up ecosystem diversity, create connectivity by protecting the corridors migratory species use, conserve remaining wilderness and preserve climate refugia — safe havens for species that cannot adapt at the pace climate change is altering their habitat.

“What we really need across Canada is a combination of approaches,” Aerin Jacob, a conservation scientist with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, told The Narwhal, agreeing that protection for species-at-risk needs to occur in the southern part of the country. But protection for large, intact wilderness areas needs to occur in the north, she said.

“What works in southern Ontario is not going to be what works in Northwest Territories.”

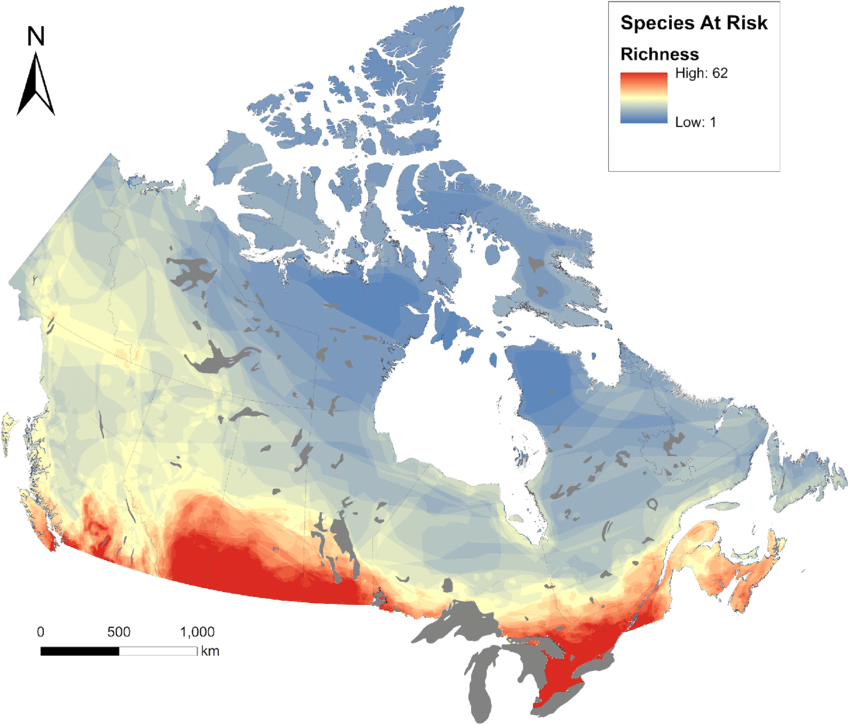

In early 2018 Coristine and Jacob published research that established five key scientific principles for identifying Canada’s high-value conservation areas: considering species-at-risk, diverse ecoregions, preserving wilderness, connectivity and climate change resilience.

The research pinpointed Canada’s conservation ‘hotspots’ and cross-referenced those with other considerations like natural resource extraction, urbanization and existing wilderness areas.

Hotspots for Canadian protected areas identified in the research of Justine Coristine, Aerin Jacob and their colleagues. This map identifies hotspots in relation to Canada’s historic land uses of urbanization, resource extraction and wilderness areas. The researchers use warm colours to “represent areas with the potential to make a greater contribution to reversing biodiversity decline and preserving biodiversity for future generations.” Map: Coristine et al.

Canada should prioritize land conservation in high-priority regions and if low-priority regions are protected, Canada should provide scientific justification for doing so, Coristine and Jacob and their co-authors wrote.

Jacob told The Narwhal that some aspects of conservation are politicized rather than scientifically founded.

No scientific research suggests aiming for specifically 17 per cent — that number, Jacob explains, is a political one.

Numerous studies have shown that in order to conserve biodiversity for future generations, 25 to 75 per cent of global land area should be protected.

While 17 per cent of terrestrial areas locked away in protected areas is a “huge step forward,” Coristine said, from a scientific perspective it’s not going to be sufficient in the long run to reduce species extinction.

Conservation progress? Who’s counting?

Another complicating factor is that some of these targets can be difficult to measure.

And progress isn’t always progress.

Earlier this year, The Narwhal reported that Canada’s big leap forward on Marine Protected Areas, from less than one per cent in 2016 to 7.75 per cent by January 2018 was actually due to a change in accounting, not new area set aside.

Rather than establishing huge protected areas, the government was counting seasonal fisheries closures as protected spaces.

Creating sustained progress, in other words, can be more challenging than the plain numbers reveal.

Politics and public perception go a long way to directing conservation goals. In order to improve Canadians engagement with and stewardship of nature, one of Canada’s four goals, is to get more Canadians out into nature.

Kelly Torck, manager of Environment and Climate Change Canada’s national biodiversity policy, told The Narwhal efforts to get more Canadians out into parks has so far been successful.

“We’ve seen a positive trend in terms of number of Canadians spending more time in nature,” Torck said. “The Canada 150 free parks pass exposed a lot more people to that.”

But that effort was one-and-done.

In the years to come, more work is needed to create lasting changes.

What about that $1.3 billion for conservation?

One of the main sources of support for this will be The Nature Fund.

In the 2018 federal budget, the government earmarked an unprecedented $1.3 billion over the next five years for the protection and conservation of nature, with $500 million committed to saving species-at-risk and establishing protected areas, as well as creating opportunities for Indigenous-led conservation efforts.

The problem with targets

The Aichi targets resemble climate targets signed onto under the Paris Accord in that both are non-binding agreements meant to fend off global catastrophe and both contain signatory countries that are way, way off track.

Such problems have led people like Shannon Hagerman, a social scientist at the University of British Columbia, to question targets-based approaches for conservation in general.

In 2016 Hagerman co-authored a case study looking at Canada’s implementation of the Aichi Targets over the five years between 2011 and 2016 and found only 28 per cent of Canada’s responses to Aichi were implemented.

Most were merely aspirational.

For Hagerman, this only led to more questions about the fundamental challenge of using targets.

“Mid-term assessments and more recent assessment confirm that almost all elements of all the targets will not be met by the achievement date,” she says.

Canada is not alone. As of December 2016, 20 per cent of reporting signatory countries had made no progress at all.

Higher income countries, however, have set weaker goals than lower-income nations and, resultantly, have reported slightly more progress.

And yet, there is an allure to announcing targets — even if they remain unmet.

“Despite these difficulties, there is still this enduring appeal of targets for environmental governance — in terms of measuring progress, enhancing accountability and promoting awareness,” Hagerman told The Narwhal.

What leaders and planners need to be careful of is replacing meaningful conservation action on the ground with too heavy of a preoccupation of global measurements.

Protected areas, for example, don’t mean much if they don’t promote connectivity between them.

“The challenge is how to solve these shortcomings,” Hagerman says.

Author Gloria Dickie is a freelance journalist who covers science and the environment, with a focus on climate change, human-wildlife conflict. . .